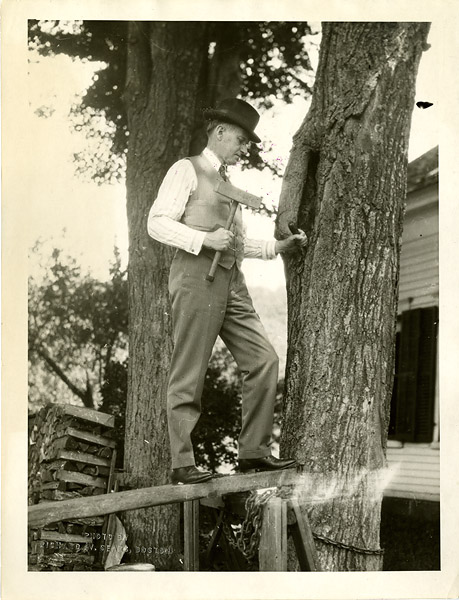

Everyone comes to learn the Presidents by different means, at various seasons of life, and in diverse forms. Most rediscover the Chief Executives once life and experience has distanced him or her from the grade level classroom. How they “meet” any of the forty-five individuals who have occupied the Presidential Office can be as engaging and impactful as the opportunity would be to find a new friend, realizing that a fascinating array of stories waits to be tapped, and an instructive human life invites introduction to you with the slightest effort on your part. The written word unlocks this potential rediscovery of a friend you may have seen as a mere name in a list or among a series of pictures that had no particular meaning or attachment to you. Yet, the Presidents can still surprise us. They certainly continue to do so for me. I meet them at times I do not always expect. Sometimes I stumble upon one of them sitting by one of my bookshelves, ready for a conversation. Some of them even appear to live with us. Other times, I catch one of the Presidents out enjoying a horseback ride in the neighborhood. Again, I happen to turn around just in time to glimpse another one walking down a stairway at the faint strains of “Hail to the Chief.” No, I do not see the dead. I see the living. The Presidents, each in their own way, lives close to each of us, if we let them enter. I first met Calvin Coolidge through the introduction of Robert Sobel. His book, Coolidge: An American Enigma, brought about a voyage of discovery I did not anticipate. Cal and Grace have now lived with us for more than two decades. They come and go whenever they please. We do not always see them at the times we might expect, for no one entirely controls the person or itinerary of Calvin and Grace Coolidge. Yet, they appear when we most need them and go when they have done all that the occasion requires. They are some of our most beloved friends. They are never late for an appointment and always know, as the gracious gentleman and lady that they are, when to speak and when to be silent, when to be on hand, ready to support, and when to leave. Not everyone will encounter them by the same means: some of our good friends first discovered them through McCoy’s The Quiet President, others through Ferrell’s The Talkative President or Fuess’ The Man from Vermont, and still others from Charles C. Johnson’s Why Coolidge Matters or Amity Shlaes’ Coolidge. A number encounter them through Mary Randolph’s Presidents and First Ladies, the Colonel’s Starling of the White House, Booraem’s The Provincial, or Lathem’s Your Son, Calvin Coolidge or Calvin Coolidge Says. Maybe it was the Curtises, in Return to These Hills, Jerry Wallace, in The First Radio President, or Robert Woods’ The Preparation of Calvin Coolidge who guided you, as Virgil and Beatrice to Dante. Paul Johnson, in Modern Times, and John Earl Haynes, in Calvin Coolidge and the Coolidge Era, have each ushered fellow travelers to the Coolidges. Edward Ransom, Niall Palmer, and other British scholars have freshened the sails when American scholarship regarding the Coolidge Twenties was at its stalest. Tom Silver’s Coolidge and the Historians sent a volley into academia when it needed to be shaken from its pretentious chronological snobbery and hypocritical misrepresentation of Cal and the decade over which he presided. Craig Fehrman, in Author in Chief, has introduced several to the remarkable literary talents Cal had while John Derbyshire, in Seeing Calvin Coolidge in a Dream, melts away the decades to reveal Cal sitting with his cigar directly across from us, as if we sat before the President a century ago. A privileged few first discover Calvin and Grace speaking directly to them in Have Faith in Massachusetts, The Price of Freedom, Foundations of the Republic, The Autobiography, or Grace’s own Autobiography. However we first encounter the Coolidges, we are now all in the same boat. Who first introduced you to Cal and Grace? Whoever it was, we rejoice to count you as our fellow sojourners. A belated Happy President’s Day, Coolidge Country!