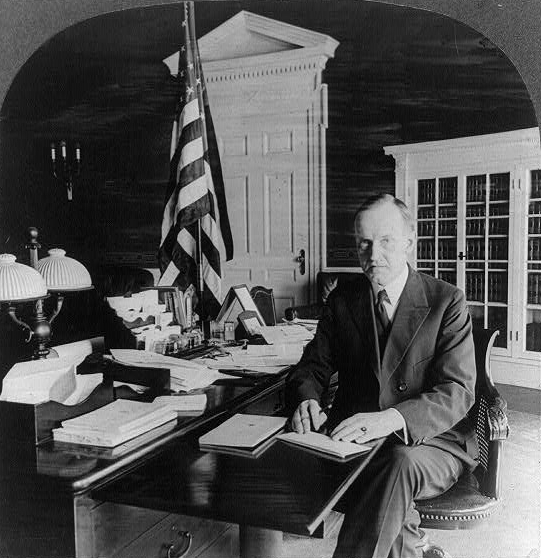

Politics to some, not excepting presidents, is a kind of contest where the image carries greater weight than the reality, intentions mean more than results and the illusion of statesmanship. Victory is seen not in terms of who fulfills the obligations of office, serving faithfully, but who appears to be the most aesthetically marketable as the face of whichever agenda emerges from within the Beltway. Conveying the impression that one cares about fiscal discipline is more important than actually cutting a single dime of government expenditure. Appointing a color, gender or ethnicity to the latest vacancy is supposed to assuage the injustice of decades of disenfranchisement as opposed to the far more substantial determination to choose men and women as individuals, on the basis of merit. Expecting the image projected to compensate for the deficit of accomplishments, politics has once again become more about the “Show Window” than the “Office Desk,” as Calvin Coolidge warned.

Having started as a member of local Republican Club and the town council in his late twenties, Coolidge would gain an exceptional measure of practical schooling in politics before ever seeing Washington. That is perhaps a large part of what gave him perspective — a quality too often lacking in the Nation’s capital — and preserved him from spoiling in office. He understood the proper ends of politics and the demands of statesmanship better than most did at the time or do today. Coolidge knew the genuine from the counterfeit. As he once observed,

“Politics is not an end, but a means. It is not a product, but a process. It is the art of government…So much emphasis has been put upon the false that the significance of the true has been obscured and politics has come to convey the meaning of crafty and cunning selfishness, instead of candid and sincere service.”

That service to which Coolidge appealed was not some calculated platitude to gain votes. He never pandered. It was a far more personal and sober duty, a serious demand upon anyone given public trust to any degree. Expecting the same commitment to service in others, he required the utmost of himself first. As one of the most important acts of the President resides in the appointment power, Coolidge could not casually exercise or flippantly regard it. Nothing less than a carefully and conscientiously selected individual could reconcile with the trust Americans had placed in their President. The merit of competence and character prevailed above color or creed when it came to Coolidge. To bestow responsibility, however authoritative the post, on the basis of nothing more than skin color or gender would be an insult to the individual and to all people. To be worthy of our representative system, Coolidge knew, government must consist of capable and trustworthy public servants. Restitution for past wrongs would not be accomplished by rewarding the unqualified. Affirmative action is simply a reverse bigotry, feeling that opportunity can only be offered and accepted with special assistance, a help based in the superficiality of color or gender preferences above the individual’s abilities and talents. When Colonel Starling sought to compliment the White House butler, Colonel Arthur Brooks, as a “fine, colored gentleman,” he met with the firm rebuke of Calvin Coolidge, “Brooks is not a colored gentleman. He is a gentleman.” The honorable old Colonel Brooks, who had not only commanded a unit of the National Guard but had served four presidents, was not an exception to the rule; this was simply Cal’s colorblind regard for everyone.

The situation was no different with Mrs. Mary Church Terrell, wife of Judge Robert Terrell of the District of Columbia. Corresponding repeatedly with the White House for the better part of a year to obtain a position in the Labor Department, Mrs. Terrell’s request was not instantly granted. An educator, journalist, founding member of the NAACP, and leader of the Women’s Republican League, Mrs. Terrell certainly possessed the credentials it seemed to deserve a job. Why then was her request, after a year of discussion, politely declined?

First, the position she wanted was already held by someone else, it would be a decidedly unfair and partial act to create a vacancy just for Mrs. Terrell, regardless of her skin color and gender.The President would be remiss in his responsibilities over the Executive Branch to judge employees in so superficial a way. Coolidge would not use the power of his Office as a tool to curry one group’s favor, however politically tenuous, nor would he use power as a weapon to rectify social inequities with token gestures.

Second, the high standards of the civil service applied to everyone equally. Each grade carried with it tests of proficiency to measure the applicant’s knowledge of that position and the work entailed. For too many years gifts of patronage were dispensed as the rewards of party loyalty and campaign work. Civil service reform had restored merit-based qualifications to government service and Coolidge held tenaciously to these standards. He would explain his approach in his Autobiography,

“…the President has a certain responsibility for the conduct of all departments, commissions and independent bureaus. While I was willing to advise with any of these officers and give them any assistance in my power, I always felt they should make their own decisions and rarely volunteered any advice. Many applications are made requesting the President to seek to influence these bodies, and such applications were usually transmitted to them for their information without comment…The parties before them are entitled to a fair trial on the merits of their case and to have judgment rendered by those to whom both sides have presented their evidence. If some one on the outside undertook to interfere, even if grave injustice was not done, the integrity of a commission which comes from a knowledge that it can be relied on to exercise its own independent judgment would be very much impaired.”

Mrs. Terrell’s case was no different. It was submitted to Mr. Henning, Acting Secretary of Labor, and Mrs. Anderson of the Women’s Bureau, who concluded that, despite Mary Terrell’s stellar resume, the civil service exams still had to be taken like everyone else. The various billets and their job descriptions with testing information was sent on to her through the White House.

Mrs. Terrell, by refusing to take the civil service examinations required to qualify for the jobs she sought, deprived herself of an opportunity in the future to be considered should an opening occur. A special appointment would neither help Mrs. Terrell, the Labor Department nor the people government is supposed to serve. Had President Coolidge intervened, it would have been a vote of no confidence in the standards of the Civil Service, the sound judgment of those closest to the situation – Mrs. Anderson and Mr. Henning, and the ability of Mrs. Terrell to shine on her own talents. She did not need a President to do for her what she already could handle through the pathway laid out by the Acting Secretary and Women’s Bureau Chief.

Third, the standards of citizenship meant more than a person’s color or ethnic background. In Secretary C. Bascom Slemp’s files of that year’s correspondence can be found a summation of Mrs. Terrell’s situation. It mattered not that she was a black woman, with all its attendant public relations points. It mattered not that she had connections with those who were suspicious, if not hostile, to the President’s approach to problems. Appointing her might help smooth rough waters. Coolidge did not operate this way. He was not, like some Presidents, who have been so desperate to please that the color or gender alone of the appointee is supposed to win friends and influence enemies. This kind of symbolism over substance was repugnant to Coolidge. In contrast, what mattered far more was whether Mrs. Terrell had voted in recent elections. She had not. In fact, an appointment would likely do more harm for race relations because of her refusal to “work well with others,” as Slemp put it. Furthermore, it would smack of even more favoritism to appoint the wife of Judge Terrell, who, despite her exceptional literary gifts and helpful organizational abilities, disqualified herself on the basis of her uncooperative personality and disinterest in exercising one of the most sacred duties of citizenship: to vote. Judged, as Dr. King dreamed, by the content of character rather than the color of her skin, Mrs. Terrell went on to contribute much toward full desegregation. She even lived to see the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, at the age of ninety.

Affirmative action did not make Bessie Coleman the first “colored” licensed aviatrix in 1922. Maggie Loan Walker did not rise to chair her own bank in the heart of Richmond through the patronage of what author Shelby Steele calls “white guilt.” Hallie Brown, whose prolific efforts as a serious writer and Republican National Committee leader, did not obtain such distinction by the good graces of Coolidge or anyone else. Her talents and hard work elevated her to success and she used her literary abilities to inspire others with a popular work, Homespun Heroines and Other Women of Distinction, published in 1926. The legal proficiency of Violette N. Anderson, graduate of Chicago Law School, would not need affirmative action to see her become the first black woman attorney to argue cases before the Supreme Court. It was a Coolidge-appointed judge who would sign her admission to so illustrious a “benchmark.” Special treatment was not at work when, under the leadership of Mary McLeod Bethune, the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, bought and paid for the first property owned fully by blacks in Washington, D.C. Coolidge would turn to her as the most qualified delegate to send to the Child Welfare Conference of 1928. She would again serve on the Memorial Commission authorized by Coolidge on his last day in office as Public Law 107. The bold Georgia D. Johnson, appointed by President Coolidge to the Labor Department conciliation bureau for her courageous competence, did much to strengthen understanding between employer and employee. The tenacity of Selena Sloan Butler to rally parents and teachers to address desegregation prevailed because she persevered not because she was a black woman. Mary Burnett Talbert, who campaigned tirelessly for the Dyer Bill, died before having seen the all-time decline of lynching by the end of the Coolidge Era. The list of accomplished ladies could go on from the political work done by Mary Montgomery Booze, the first of several women leaders in the Republican National Committee from the 1920s onward to the athletic triumphs of Tuskegee’s all-women track team, established in 1927. The success these women attained despite “Jim Crow” was not handed to them, they had to go out and earn it. These were all achievements done without affirmative action, the policy that racial prejudice can only be overcome by special treatment rather than individual hard work and determination.

When Coolidge signed Public Law 107 in his last few hours in office, March 4, 1929, creating a “National Memorial Commission” charged with the construction of “a memorial building suitable for meetings of patriotic organizations, public ceremonial events, the exhibition of art and inventions…as a tribute to the Negro’s contribution to the achievements of America” he was not engaging in cheap political concessions. Coolidge could have left this business for his successor but this first step was not an attempt to bolster popularity, it was another way of showing his regard for every American, approving an institution that all could participate in, that would exclude none and from which all could learn that skin color hardly precluded great contributions to America. On the contrary, a host of men and women deserved full recognition not because of their blackness but for the character they displayed and the great things they did to make this Republic better than they found it, commending her noblest ideals and championing individual service, not government servitude, as the means of mutual respect and peaceful assimilation. It was the same honor shown throughout Coolidge’s tenure, from his recognition of Norse contributions to America at the Norwegian Centennial in 1925 to the marks left by the South at his speech in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1926. Coolidge was working to continue healing old wounds and reminding Americans of their shared ideals, not their external differences. The law was buried by the Democratic Congress soon thereafter and the Commission scrapped by F.D.R. in 1934. Not until December 2001 would another President, George W. Bush, revive the law and restore the Commission’s work.

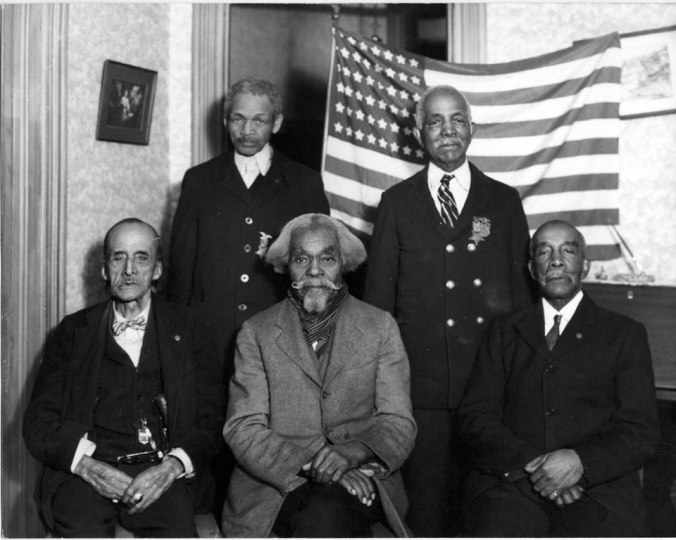

Some of the Grand Army of the Republic who began the work back in 1915 that pushed for a memorial honoring the contributions of Negroes in America. This picture was taken of them in 1935, as the fight continued to act on what Coolidge had authorized six years before.

As Coolidge would write to a Charles Gardner of New York on August 9, 1924,

“Our Constitution guarantees equal rights to all our citizens, without discrimination on account of race or colour. I have taken my oath to support that Constitution. It is the source of your rights and my rights. I propose to regard it, and administer it, as the source of the rights of all the people, whatever their belief or race. A coloured man is precisely as much entitled to submit his candidacy in a party primary as is any other citizen. The decision must be made by the constituents to whom he offers himself, and by nobody else. You have suggested that in some fashion I should bring influence to bear to prevent the possibility of a coloured man being nominated for Congress. In reply, I quote my great predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt: ‘…I cannot consent to take the position that the door of hope–the door of opportunity–is to be shut upon any man, no matter how worthy, purely upon the grounds of race or colour.’ “

Just as Coolidge would not shut that door of opportunity because of a person’s color or race nor would he prop it open to grant color or race preeminent consideration above the responsibilities of competence and character in order to appear magnanimous and “tolerant.” Just being black, a minority or a woman did nothing for Coolidge. He saw beyond those non-essentials to the real person. Were he to intervene, using Presidential power to override legitimate disqualification for the sake of color or gender, it would not only impose a new unfairness, punishing the capable, but would also reject the trust people placed upon the Office he held. For him, the public trust was too precious to subordinate it to the expedience of the moment, succumbing to an abhorrent form of reverse racism that is now embedded in affirmative action.