Few men have been as singularly characterized by one misquotation as Calvin Coolidge. It is ironic that of all the misrepresented statements which could be made of our thirtieth President, the one incessantly parroted derives from a speech to the American Society of Newspaper Editors. If anyone is supposed to be curious enough to check their facts, research context and accurately report what is found, is it not the press?

Yet, each time, “the business of America is business” is the final word echoed on all that is ever worth knowing about the man and his era, those greedy, materialistic Twenties. Thank you, William Allen White. This “sound-byte” premise sets up a convenient marketing contrast for what came after in the charismatic person of F.D.R. and his “triumph” over economic depression made possible through the “New Deal.” Now just short of ninety years since Coolidge spoke to those members of the press on January 17, 1925, it becomes obvious to anyone who actually reads this speech in full that “Silent Cal” was not claiming business rightly functioned as the end-all of American existence. He was asserting the opposite. The same man who, in actuality, said, “The chief business of the American people is business” also said in the next paragraph, “The chief ideal of the American people is idealism.” He was lauding ideals, the spiritual commodities that accrue to character: peace, honor and charity, and the integrity of the soul, not the absorption in materialism.

If anything, looking at what the media has become, Coolidge was ahead of his time, identifying the very methods the Left has incrementally used to dominate modern education and deploy the “sources of public information” as purveyors of propaganda rather than sound information. These sources have become exactly what Coolidge warned they would be if the press succumbed to autocratic government.

President Coolidge, on the White House grounds, reviews plans for the National Press Building later that same year, September 15, 1925.

In his ability to see the danger and explain it, Coolidge’s wisdom is a threat to a news media subservient to those in power. This is why he has been lampooned and caricatured, his statements yanked from context and his credibility discounted by the self-appointed “smartest of the smart.” He refuses to fit neatly into the box built for him all these years by the political and cultural elite, who now rule in alliance with each other. It is this speech, perhaps more cogently than any other, that exposes their motivations and procedures for what they are. He entered into their arena and is it any wonder that Coolidge has been so vilified and maligned for it? To restore Coolidge to his rightful position and his words to their proper perspective would be the beginning of the end for this modern regime. It is, after all, a ruling class of politicians and propagandists who can only retain legitimacy through the perpetuation of ignorance, the maintenance of false standards, and the perverse union between those devoted to power rather than committed to the truth. This elite caste serves the ideological interests of a few rather than the “general interest of the whole people.” Freedom cannot endure without truth.

President Coolidge poses with the Washington correspondents corps on the lawn of the White House, August 14, 1923. The press, not without its biases and healthy curiosity even then, remained fair to Coolidge throughout his five years and seven months in office. Coolidge had his detractors, like correspondent Frank Kent, Charles Michaels and others, but none walked in the unquestioned conformity they largely do today. Coolidge could honestly assess their coverage in these terms: “You have been, I think, quite successful in interpreting the administration to the country. I have known that I wasn’t much of a success in undertaking newspaper work, so I have left the work of reporting the affairs of my administration to the experts of the press. Perhaps that is the reason that the reports have been more successful than they would have been if I had undertaken myself to direct them” (March 1, 1929, The Talkative President, p. 34). Coolidge practiced what he preached, letting the press do their job, free of fabricated “facts” or political strategy directives on what to report from the White House.

Here it is, President Coolidge’s speech to the American Society of Newspaper Editors in full:

“The relationship between governments and the press has always been recognized as a matter of large importance. Wherever despotism abounds, the sources of public information are the first to be brought under its control. Wherever the cause of liberty is making its way, one of its highest accomplishments is the guarantee of the freedom of the press. It has always been realized, sometimes instinctively, oftentimes expressly, that truth and freedom are inseparable. An absolutism could never rest upon anything save a perverted and distorted view of human relationships and upon false standards set up and maintained by force. It has always found it necessary to attempt to dominate the entire field of education and instruction. It has thrived on ignorance. While it has sought to train the minds of a few, it has been largely with the purpose of attempting to give them a superior facility for misleading the many. Men have been educated under absolutism, not that they might bear witness to the truth, but that they might be the more ingenious advocates and defenders of false standards and hollow pretenses. This has always been the method of privilege, the method of class and caste, the method of master and slave.

“When a community has sufficiently advanced so that its government begins to take on that of the nature of a republic, the processes of education become even more important, but the method is necessarily reversed. It is all the more necessary under a system of free government that the people should be enlightened, that they should be correctly informed, than it is under an absolute government that they should be ignorant. Under a republic the institutions of learning, while bound by the constitution and laws, are in no way subservient to the government. The principles which they enunciate do not depend for their authority upon whether they square with the wish of the ruling dynasty, but whether they square with the everlasting truth. Under these conditions the press, which had before been made an instrument for concealing or perverting the facts, must be made an instrument for their true representation and their sound and logical interpretation. From the position of a mere organ, constantly bound to servitude, public prints rise to a dignity, not only of independence, but of a great educational and enlightening factor. They attain new powers, which it is almost impossible to measure, and become charged with commensurate responsibilities.

“The public press under an autocracy is necessarily a true agency of propaganda. Under a free government it must be the very reverse. Propaganda seeks to present a part of the facts, to distort their relations, and to force conclusions which could not be drawn from a complete and candid survey of all the facts. It has been observed that propaganda seeks to close the mind, while education seeks to open it. This has become one of the dangers of the present day.

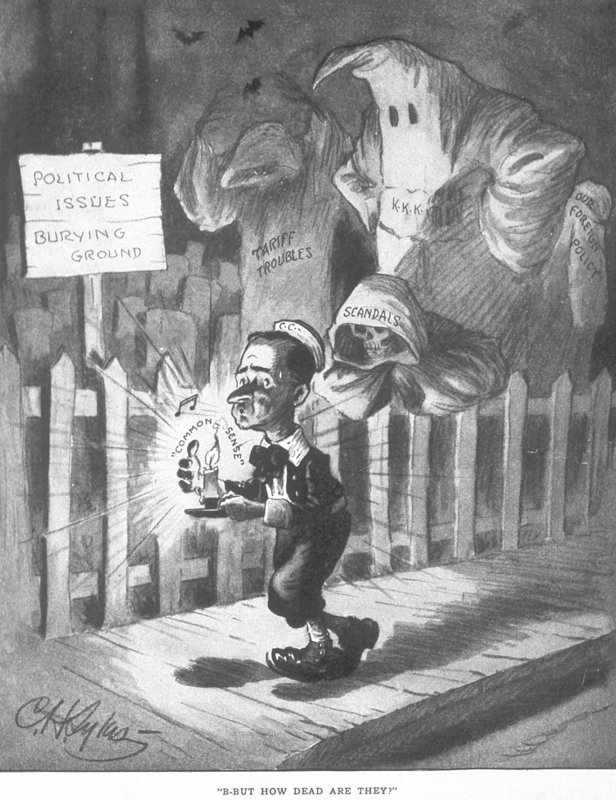

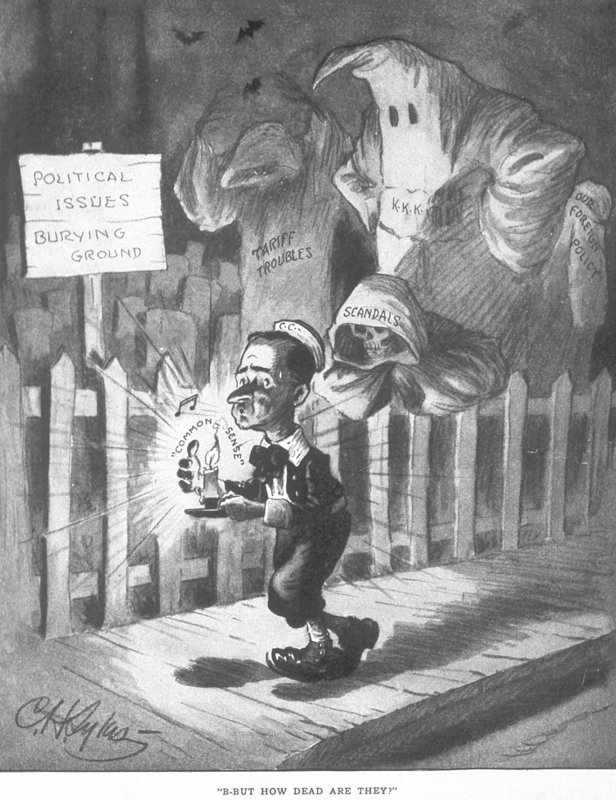

Cartoon by C.H. Sykes appearing in Life magazine, October 2, 1924.

“The great difficulty in combating unfair propaganda, or even in recognizing it, arises from the fact that at the present time we confront so many new and technical problems that it is an enormous task to keep ourselves accurately informed concerning them. In this respect, you gentlemen of the press face the same perplexities that are encountered by legislators and government administrators. Whoever deals with current public questions is compelled to rely greatly upon the information and judgments of experts and specialists. Unfortunately, not all experts are to be trusted as entirely disinterested. Not all specialists are completely without guile. In our increasing dependence on specialized authority, we tend to become easier victims for the propagandists, and need to cultivate sedulously the habit of the open mind. No doubt every generation feels that its problems are the most intricate and baffling that have ever been presented for solution. But with all recognition of the disposition to exaggerate in this respect, I think we can fairly say that our times in all their social and economic aspects are more complex than any past period. We need to keep our minds free from prejudice and bias. Of education, and of real information we cannot get too much. But of propaganda, which is tainted or perverted information, we cannot have too little.

“Newspaper men, therefore, endlessly discuss the question of what is news. I judge that they will go on discussing it as long as there are newspapers. It has seemed to me that quite obviously the news-giving function of a newspaper cannot possibly require that it give a photographic presentation of everything that happens in the community. That is an obvious impossibility. It seems fair to say that the proper presentation of the news bears about the same relation to the whole field of happenings that a painting does to a photograph. The photograph might give the more accurate presentation of details, but in doing so it might sacrifice the opportunity the more clearly to delineate character. My college professor was wont to tell us a good many years ago that if a painting of a tree was only the exact representation of the original, so that it looked just like the tree, there would be no reason for making it; we might as well look at the tree itself. But the painting, if it is of the right sort, gives something that neither a photograph nor a view of the tree conveys. It emphasizes something of character, quality, individuality. We are not lost in looking at thorns and defects; we catch a vision of the grandeur and beauty of a king of the forest.

“And so I have conceived that the news, properly presented, should be a sort of cross-section of the character of current human experience. It should delineate character, quality, tendencies and implications. In this way the reporter exercises his genius. Out of the current events he does not make a drab and sordid story, but rather an informing and enlightened epic. His work becomes no longer imitative, but rises to an original art.

Portrait of Coolidge by Hungarian artist Philip de Laszlo, 1926.

“Our American newspapers serve a double purpose. They bring knowledge and information to their readers, and at the same time they play a most important part in connection with the business interests of the community, both through their news and advertising departments. Probably there is no rule of your profession to which you gentlemen are more devoted than that which prescribes that the editorial and the business policies of the paper are to be conducted by strictly separate departments. Editorial policy and news policy must not be influenced by business consideration; business policies must not be affected by editorial programs. Such a dictum strikes the outsider as involving a good deal of difficulty in the practical adjustments of every-day management. Yet, in fact, I doubt those adjustments are any more difficult than have to be made in every other department of human effort. Life is a long succession of compromises and adjustments, and it may be doubted whether the press is compelled to make them more frequently than others do.

“When I have contemplated these adjustments of business and editorial policy, it has always seemed to me that American newspapers are peculiarly representative of the practical idealism of our country. Quite recently the construction of a revenue statute resulted in giving publicity to some highly interesting facts about incomes. It must have been observed that nearly all the newspapers published these interesting facts in their news columns, while very many of them protested in their editorial columns that such publicity was a bad policy. Yet this was not inconsistent. I am referring to the incident by way of illustrating what I just said about the newspapers representing the practical idealism of America. As practical newsmen they printed the facts. As editorial idealists they protested that there ought to be no such facts available.

“Some people feel concerned about the commercialism of the press. They note that great newspapers are great business enterprises earning large profits and controlled by men of wealth. So they fear that in such control the press may tend to support the private interests of those who own the papers, rather than the general interest of the whole people. It seems to me, however, that the real test is not whether the newspapers are controlled by men of wealth, but whether they are sincerely trying to serve the public interests. There will be little occasion for worry about who owns a newspaper, so long as its attitudes on public questions are such as to promote the general welfare. A press which is actuated by the purpose of genuine usefulness to the public interest can never be too strong financially, so long as its strength is used for the support of popular government.

Coolidge standing for the farewell picture with White House correspondents, February 26, 1929.

“There does not seem to be cause for alarm in the dual relationship of the press to the public, whereby it is one one side a purveyor of information and opinion and on the other side a purely business enterprise. Rather, it is probable that a press which maintains an intimate touch with the business currents of the nation, is likely to be more reliable than it would be if it were a stranger to these influences. After all, the chief business of the American people is business. They are profoundly concerned with producing, buying, selling, investing and prospering in the world. I am strongly of opinion that the great majority of people will always find these are moving impulses of our life. The opposite view was oracularly and poetically set forth in those lines of Goldsmith which everybody repeats, but few really believe:

‘Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey,

‘Where wealth accumulates, and men decay.’

“Excellent poetry, but not a good working philosophy. Goldsmith would have been right, if, in fact, the accumulation of wealth meant the decay of men. It is rare indeed that the men who are accumulating wealth decay. It is only when they cease production, when accumulation stops, that an irreparable decay begins. Wealth is the product of industry, ambition, character and untiring effort. In all experience, the accumulation of wealth means the multiplication of schools, the increase of knowledge, the dissemination of intelligence, the encouragement of science, the broadening of outlook, the expansion of liberties, the widening of culture. Of course, the accumulation of wealth cannot be justified as the chief end of existence. But we are compelled to recognize it as a means to well-nigh every desirable achievement. So long as wealth is made the means and not the end, we need not greatly fear it. And there never was a time when wealth was so generally regarded as a means, or so little regarded as an end, as today.

“Just a little time ago we read in your newspapers that two leaders of American business, whose efforts at accumulation had been most astonishingly successful, had given fifty or sixty million dollars as endowments to educational works. That was real news. It was characteristic of our American experience with men of large resources. They use their power to serve, not themselves and their own families, but the public. I feel sure that the coming generations, which will benefit by those endowments, will not be easily convinced that they have suffered greatly because of these particular accumulations of wealth.

President Coolidge with members of the White House Photographers Association, 1923.

“So there is little cause for the fear that our journalism, merely because it is prosperous, is likely to betray us. But it calls for additional effort to avoid even the appearance of the evil of selfishness. In every worthy profession, of course, there will always be a minority who will appeal to the baser instinct. There always have been, and probably always will be some who will feel that their own temporary interest may be furthered by betraying the interest of others. But these are becoming constantly a less numerous and less potential element in the community. Their influence, whatever it may seem at a particular moment, is always ephemeral. They will not long interfere with the progress of the race which is determined to go its own forward and upward way. They may at times somewhat retard and delay its progress, but in the end their opposition will be overcome. They have no permanent effect. They accomplish no permanent result. The race is not traveling in that direction. The power of the spirit always prevails over the power of the flesh. These furnish us no justification for interfering with the freedom of the press, because all freedom, though it may sometime tend toward excesses, bears within it those remedies which will finally effect a cure for its own disorders.

“American newspapers have seemed to me to be particularly representative of this practical idealism of our people. Therefore, I feel secure in saying that they are best newspapers in the world. I believe that they print more real news and more reliable and characteristic news than any other newspaper. I believe their editorial opinions are less colored in influence by mere partisanship or selfish interest, than are those of any other country. Moreover, I believe that our American press is more independent, more reliable and less partisan today than at any other time in its history. I believe this of our press, precisely as I believe it of those who manage our public affairs. Both are cleaner, finer, less influenced by improper considerations, than ever before. Whoever disagrees with this judgment must take the chance of marking himself as ignorant of conditions which notoriously affected our public life, thoughts and methods, even within the memory of many men who are still among us.

“It can safely be assumed that self-interest will always place sufficient emphasis on the business side of newspapers, so that they do not need any outside encouragement for that part of their activities. Important, however, as this factor is, it is not the main element which appeals to the American people. It is only those who do not understand our people, who believe that our national life is entirely absorbed by material motives. We make no concealment of the fact that we want wealth, but there are many other things that we want very much more. We want peace and honor, and that charity which is so strong an element of all civilization. The chief ideal of the American people is idealism. I cannot repeat too often that America is a nation of idealists. That is the only motive to which they ever give any strong and lasting reaction. No newspaper can be a success which fails to appeal to that element of our national life. It is in this direction that the public press can lend its strongest support to our Government. I could not truly criticize the vast importance of the counting, room, but my ultimate faith I would place in the high idealism of the editorial room of the American newspaper.”

“The New Editor Goes to Work” by Jay “Ding” Darling, as former President Coolidge joined the editorial room as a daily columnist in the summer of 1930.

It is both illustrative and ironic that the most frequently misquoted statement used to misrepresent Coolidge’s character was prompted by a speech on the danger of institutionalized media bias. Having so successfully relegated Coolidge to the oblivion of a weak, do-nothing President for so long, the modern mainstream of news coverage is content to keep him marginalized indefinitely. As a much older Massachusetts man once said, however, “facts are stubborn things.” A media that, over the course of nine decades, has betrayed their trust as independent and open-minded “sources of public information,” for the benefit of the entire people, is no longer living up to that practical idealism Coolidge knew to be essential for free and popular government. Freedom and truth are inseparable. Either America will remain free and soundly informed or enslaved and ignorant, it cannot be both ways. Our country will not retain political and economic liberty without intellectual and spiritual freedom. Instead, far too many have given themselves over to a slavish adherence to propaganda, closing minds in order to advance the interests of despotic and autocratic politicians.

What some have ridiculed as Coolidge’s “patriotic journalism,” is simply interpreting human experience anchored by a conscientious and careful integrity instead of through the lens of distorted facts, withheld information, suppressed moral standards and a wholesale denial that biases exist everywhere, even among the media and the “experts” on which they rely. The major networks and news sources have donned a cloak of “objectivity” for so long, they are convinced by the self-delusion that journalism requires no obligation to either the American people or their founding ideals. Enslaved by their own closed-minded fidelity to partisan power, many in the press have mentally and morally renounced citizenship as Americans and the duty they once held to all the people, furnishing them a press free and independent of government.

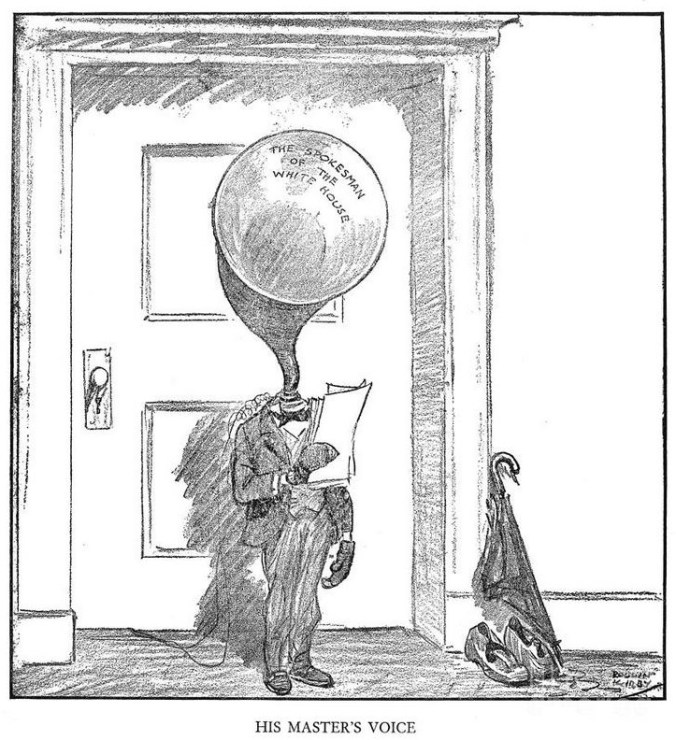

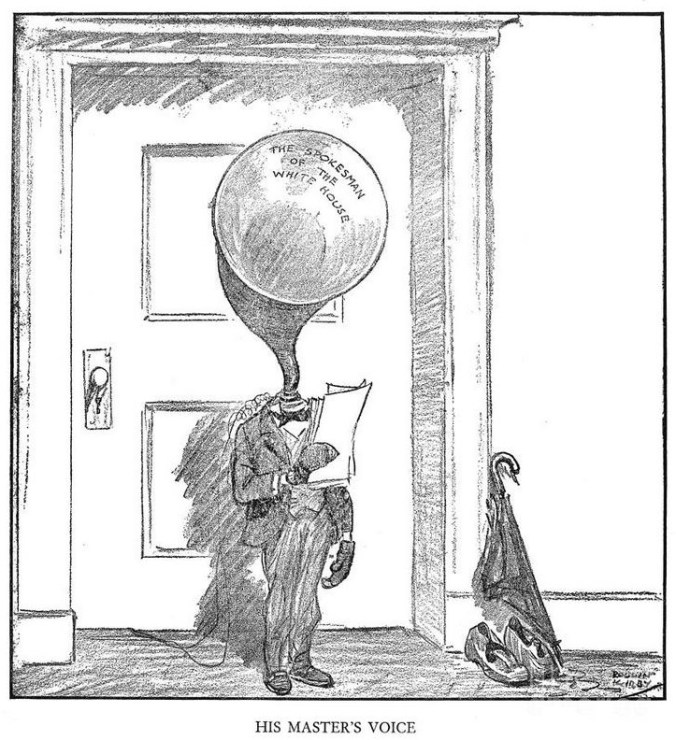

By Rollin Kirby in the New York World, February 11, 1926. The “White House spokesman” was a rhetorical device employed by the press corps when referring to a position of the White House. Coolidge never authorized its use and, in fact, detested it, especially as it became an obvious reference to the President himself despite express requests never to quote him directly. Nevertheless, it took on a life of its own as portrayed by Kirby in the cartoon above. See Coolidge’s thoughts on the matter in The Talkative President, p. 30.

Coolidge understood that both the business side and editorial sphere of media serve distinct purposes. This is as it should be. They remain separate for a reason. It is the suicide of a free press when what is newsworthy benefits the image and agenda of authority at the expense of those in “flyover country.” Likewise, when news sources disconnect from the business life of America, cutting themselves off from the practical considerations of regular Americans, the credibility of journalism is lost. Attacking America’s people and heritage, character and accomplishments, constitutional and economic institutions, focusing only on its failures and defects while ignoring its goodness and successes will only squander the opportunity to educate, inform and progress. It does not work here. We expect such cynical misunderstanding of America by international media, not by our own press. The mainstream press, so long insulated from the rest of us as strangers in a place they consider foreign to them, are losing to the new media for this reason.

The success of Rush Limbaugh, Matt Drudge and others like them is not due to some mystical indoctrination method, it is due to simply explaining what we already know to be true, credible and right. They have tapped into an open-minded and highly information-literate American audience finished with the incessant suppression of factual reporting by a correspondent corps subservient to those in office. Americans expect high standards from journalism and we will not condone those who engage in half-truths and unquestioned propaganda on behalf of state-approved authority, moving at purposes without our consent and designs hostile to our free system. The very real good of an independent and honest press comes, just as Coolidge reminded us eighty-nine years ago, from a genuine commitment to the character and ideals Americans work to live up to every day. The truth matters to us and in order to preserve our republican form of government, we return to what Coolidge dubbed “practical idealism,” the rigorous standards of a new press unafraid to meet is obligations, reapplying the practices the mainstream press once did. America’s new media, such as Rush and Breitbart, are justifying Calvin Coolidge’s enduring faith, not in the counting room, but in the editorial rooms of America’s real journalists.

“[T]he accumulation of wealth cannot be justified as the chief end of existence … So long as wealth is made the means and not the end, we need not greatly fear it…Important, however, as this factor is, it is not the main element which appeals to the American people. It is only those who do not understand our people, who believe that our national life is entirely absorbed by material motives” — Calvin Coolidge, January 17, 1925, emphasis added.