One of the unheralded heroes on Inauguration Day a century ago was legendary radio announcer Graham McNamee. He had already initiated the now familiar tradition of giving historical context and commentary to the news in President Coolidge’s first Annual Message in December 1923. McNamee’s image, wired from the resplendent Public Auditorium in Cleveland the previous summer while covering the Republican National Convention, became one of the first transmitted by the rapidly accelerating powers of the medium. The transmission, just developing at the time, took four minutes. His work for WEAF remained on the cutting edge as he was set to cover the Presidential Inaugural Address in March 1925, the first in history to be carried by radio. It was estimated by correspondents at the time that between 22 to 25 million people heard the Inaugural, including the full recording of Coolidge’s 4,000 plus word Address. Carried across twenty-two stations spanning coast-to-coast, the still novel technology captured the sounds of the pages and the President’s voice so crisply (including more than one of his inspirations!) that he seemed to be on the stage of nearly every school gym and public gathering in the country at the same, shared moment in time. It was America’s first synchronized experience of a vital cultural and political tradition, carrying with implications set to transcend the constraints of the globe itself. Yet, well on his way to earning the Radio Digest Award that year as the “World’s Most Popular Radio Announcer,” McNamee almost missed the entire occasion.

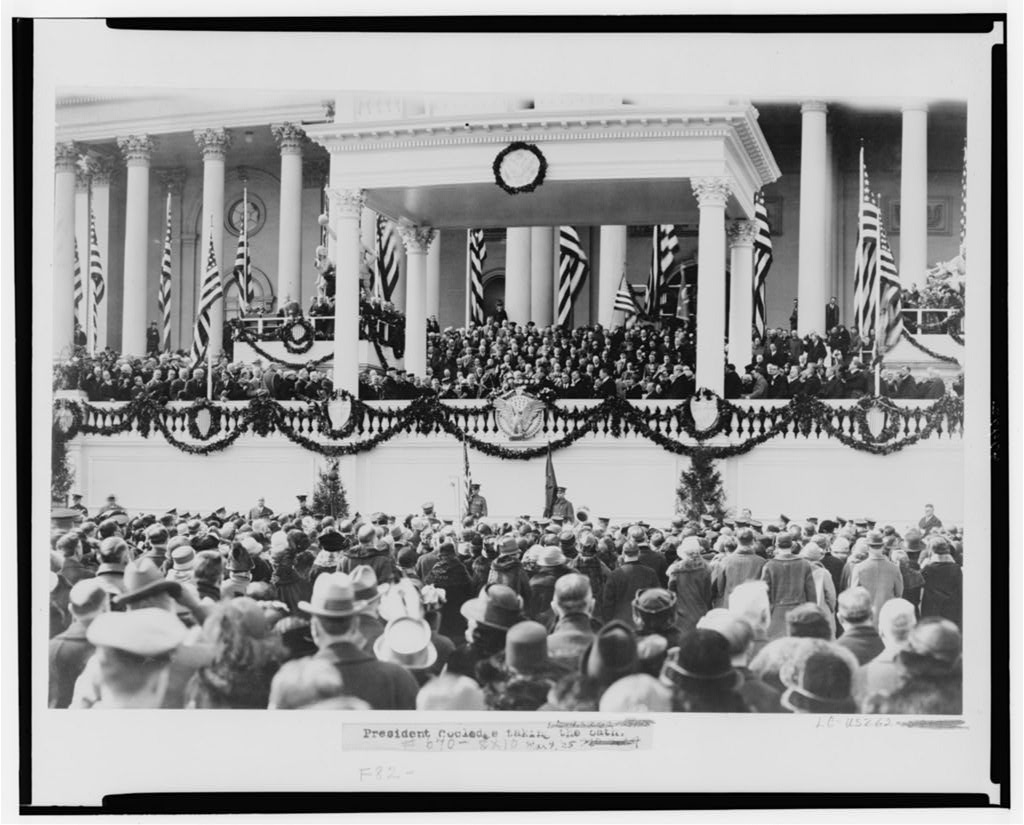

McNamee recalled it this way: “The inauguration proved a meaner job than most, as it was so hard to get information. Washington was full of officials, each apparently knowing all about what was to take place but unwilling to impart much of their knowledge. Everything was confusion, likewise everybody was passing the buck; and it was almost impossible to make our arrangements. For one thing we didn’t know when to go on the air.” It was predicated, McNamee explained, on how long the vice-presidential oath and ceremonies in the Senate Chamber took. It could be twenty minutes or an hour. No telephone wires were permitted in the Senate and so word had to be carried by runner. “Yet,” McNamee continued, “once on the air we had to stay on.” The announcer had to be ready to innovate, crafting the role of political commentator along the way. “So again I wrote reams of stuff, historical stories, and so on, as filler-in-material. Meantime I had stationed messengers in the capitol to hot-foot it to me as soon as the President and Vice-president left the Senate Chamber to come to the capitol steps, where the President himself was to take the oath of office.”

Then it happened. “I got lost and the radio sets were almost left flat without an announcer,” McNamee recalled. “My booth was on the pedestal of one of the statues by the steps of the capitol; and all the messengers being busy, I left the booth for a minute, while the officials were still in the Senate Chamber, to get word to one of our staff. To reach him I had to hurdle a temporary fence built to keep the President’s pathway clear of intruders; and, once on the other side, I found I couldn’t get back. A patrolmen yanked me by the shoulder just as I was climbing over on the return journey, and refused to let me go further. I vain I pleaded: ‘Against orders,’ he said. I told him of the microphone lying silent and pictured all the people from coast to coast that would be disappointed. But he was evidently a man of a single-track mind, one of those burly and not very imaginative policemen that will stick like a bulldog to an order, once they get it, and who are inflexible when given a little authority.”

It became desperately close to time. “For ten minutes I argued until at last I saw light–another way of approach through the crowd, which I had not noticed before. I asked him about it; that was all right–it was out of his jurisdiction, but never would he have let me over that fence in spite of the waiting twenty-five million. And that was the total estimated by the newspapers, the audience on this occasion being vastly increased by the children. Almost every school in the land had a loud-speaker installed in its auditorium or its one little room, in the case of the country hamlets.”

McNamee got back to his booth just in time. “And at that I was caught, for after I reached the booth, and went on the air, with a little description, then a story, I was halfway through that story when a messenger came racing to me, saying that the procession had started from the Senate Chamber. We were having difficulty enough in timing things, anyway, and General Dawes upset even our tentative calculations. Instead of swearing-in the senators one by one, he had done it in batches. That story was pretty well jumbled, I am afraid, for the President was on its heels. I had to cut off my microphone quickly and signal the control room to put on the President’s microphone, just in time to catch the administration of the oath of office by Chief Justice Taft.”

“The President stood there very quietly, looking subdued and careworn, I thought; this was so soon after his boy’s death; and his reply to the oath was so low that none of the people there present, excepting the few immediately around him, and none of the radio audience, heard it. We answered many inquiries by mail, afterwards, telling them that the response was a simple, ‘I do.’ ”

Read more about the legendary Graham McNamee in Salient Cal’s America: Reappraising the Harding & Coolidge Era. Thanks to McNamee and his excellent team’s work, here is an excerpt of President Coolidge’s Inaugural Address (which was recorded in full, at the time), the first of its kind carried via radio a century ago.