As Liberty and Rush Revere take every reading list by storm across the country, this day observes not only the honor we render to our veterans but also the day the Pilgrims committed themselves to the rule of law through the Mayflower Compact in 1620. Derided as “Puritans” for their belief in the sanctity of conscience, committed to live by higher standards than the mediocre choices made for them by the King, the Pilgrims separated themselves from the coercive government of England for the freedoms, first, of Holland and then after two treacherous months crossing the Atlantic, the risks and opportunities of the New World. Still aboard the Mayflower on this day in November, three hundred ninety-three years ago, thirty-one Pilgrims signed the first charter of government by consent in the New World, binding all under the authority of just and equal laws. Their courage, faith and exceptional sense of purpose — risking everything for the fundamental truth of the God-given liberty of conscience — set America from the start on a vastly different foundation than the accepted norm practiced by the rest of the world’s despotic and lawless governments.

It was Governor Coolidge who saw the cause joined for which both the Pilgrims sacrificed and our veterans’ sacrifices now of everything in this life so that we would attain a society not subsisting at the behest of government force but thriving under the reign of law over governor and governed alike. In official proclamation, Coolidge declared, “War is the rule of force. Peace is the reign of law. When Massachusetts was settled the Pilgrims first dedicated themselves to a reign of law. When they set foot on Plymouth Rock they brought the Mayflower Compact, in which, calling on the Creator to witness, they agreed with each other to make just laws and render due submission and obedience. The date of that American document was written November 11, 1620.

“After more than five years of the bitterest war in human experience, the last great stronghold of force, surrendering to the demands of America and her allies, agreed to cast aside the sword and live under the law. The date of that world document was written November 11, 1918.”

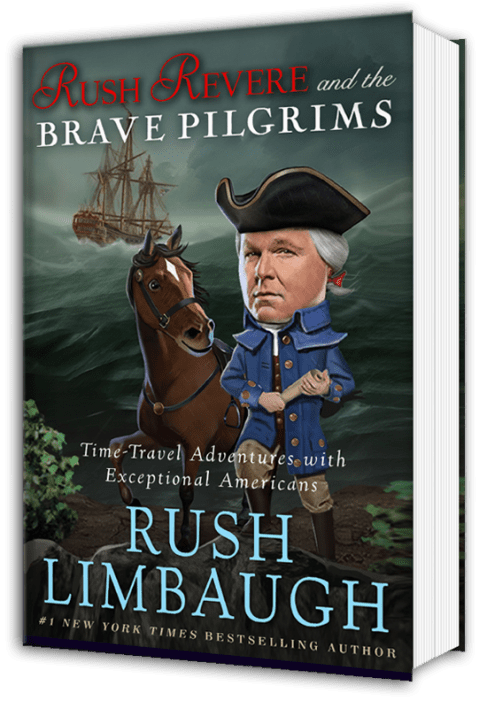

Rush Limbaugh’s look at the historical record restores an unjustly excised chapter from our exceptional American life. It simply is not being learned by our children under the stifling regime of modern education. Americans, thanks to this superb book, are being taught again what Coolidge and his generation not only knew by heart, humbly cherished with warranted pride, but found from those men, women and children, despised and rejected by tyrants and despots, an inspiration to greater faith and perpetuation of exceptional achievements.

In a history replete with exceptional people of all kinds, Coolidge held these Pilgrims, who left all they knew to undergo hardships we do not even approach today, with the highest esteem and admiration. No trivial reason drove them to so profound a step into the unfamiliar and deadly in order to secure the blessings of freedom endowed, not by monarchs or Parliaments, but by our Creator.

The Coolidges looking up toward the memorial to the Pilgrims, Plymouth, Massachusetts

The Coolidges looking up toward the memorial to the Pilgrims, Plymouth, Massachusetts

As Coolidge speaks, in his own account of those brave Pilgrims, we can hear in his words the enthusiasm and reverence for the moral power of their example, a force that no arbitrary force, however strong, can withstand. An unchallenged management of every choice in life from Washington can only and absolutely succeed, not by disarming the people physically but by severing Americans from their history — disarming the people intellectually and spiritually. Coolidge spoke then and Rush speaks now so that we retain the long memory of our liberties, as it resists the slow, yet destructive, encroachments of those who sincerely believe they are acting for our own good.

Addressing the National Geographic Society in 1923, Coolidge recounts the Pilgrim’s exceptional accomplishment, “Whatever power is lodged in a monarch, always he has sought to maintain and extend it by encroachment upon the liberties of the people. When the more advanced of the Puritans sought to put their principle of freedom into practical effect by separation from the established church, they were met by the notorious threat of the King that he would make them conform or he would harry them out of the land.

“In that threat lay the foundation of Massachusetts. That little band, from among whom were to come those made forever immortal by that voyage of the Mayflower, sought refuge in Holland, where, by an edict of William the Silent, freedom of religion had been established…”

Citing the words of their preacher, John Robinson, Coolidge continued, ” ‘The people…are industrious and frugal. We are knit together as a body in a most sacred covenant of the Lord, of the violation whereof we hold ourselves strictly tied to all care of each others’ good and of the whole by every one, and so mutually. It is not with us as with men whom small things can discourage.’ In that simple statement is to be found,” Coolidge summarized, “the principle of prosperity, responsibility, and social welfare, all based on religion.” That was not the end of the story, however. “They were of humble origin,” Coolidge noted. These families were not living high on the backs of the poor. They did not get where they were going by confiscation or oppression of others. “The bare necessities of existence had been won by them in a strange country only at the expense of extreme toil and hardship. They did not shrink from the prospect of a like experience in America…

“It was such a people, strengthened by such a purpose, obedient to such a message, who set their course in the little Mayflower across the broad Atlantic on the sixth day of September, 1620…

“A providential breeze carried them far to the north, while storms and the frail condition of their ship prevented them from continuing to their destination. They came to anchor off Provincetown far outside the jurisdiction of their own patent and the authority of existing laws…

“Undismayed they set about to establish their own institutions and recognize their own civil authority. Gathering in the narrow cabin of the Mayflower, piously imploring the divine presence, in mutual covenant they acknowledged the power ‘to enacte, constitute, & frame just & equall lawes, ordinances, actes, constitutions & offices,’ to which they pledged ‘ all due submission & obedience.’ So there was adopted the famous Mayflower Compact. It did not in form establish a government, but it declared the authority to establish a government, the power to make laws, and the duty to obey them. Beyond this it proclaimed the principle of democracy. The powers which they proposed to exercise arose directly from the express consent of all the governed. The date of this document, remarkable for what it contains, but more remarkable still because it reveals the capacity and spirit of those who made it, is November 11, 1620, old style; under the new calendar it is destined long to be remembered as Armistice Day…

The Coolidges visiting the memorial marker of William Bradford, leader of the Plymouth settlement

The Coolidges visiting the memorial marker of William Bradford, leader of the Plymouth settlement

“Such was the beginning of Massachusetts, men and women humble in position, few in numbers, seemingly weak, but possessed of a purpose, moved by a deep conviction, guided by an abiding spirit, against which both time and death were powerless. It is said that upon the old Colony of Plymouth there is no stain of bigoted persecution. They carried with them the atmosphere of holy charity. Their efforts and their experience stand forth distinctly, raising a new hope in the world…” Indeed, they still do, inspiring even the youngest Americans among us to love and share the same great principles those brave Pilgrims demonstrated nearly four centuries ago.

Pilgrims signing the Compact aboard the Mayflower, November 11, 1620

Pilgrims signing the Compact aboard the Mayflower, November 11, 1620