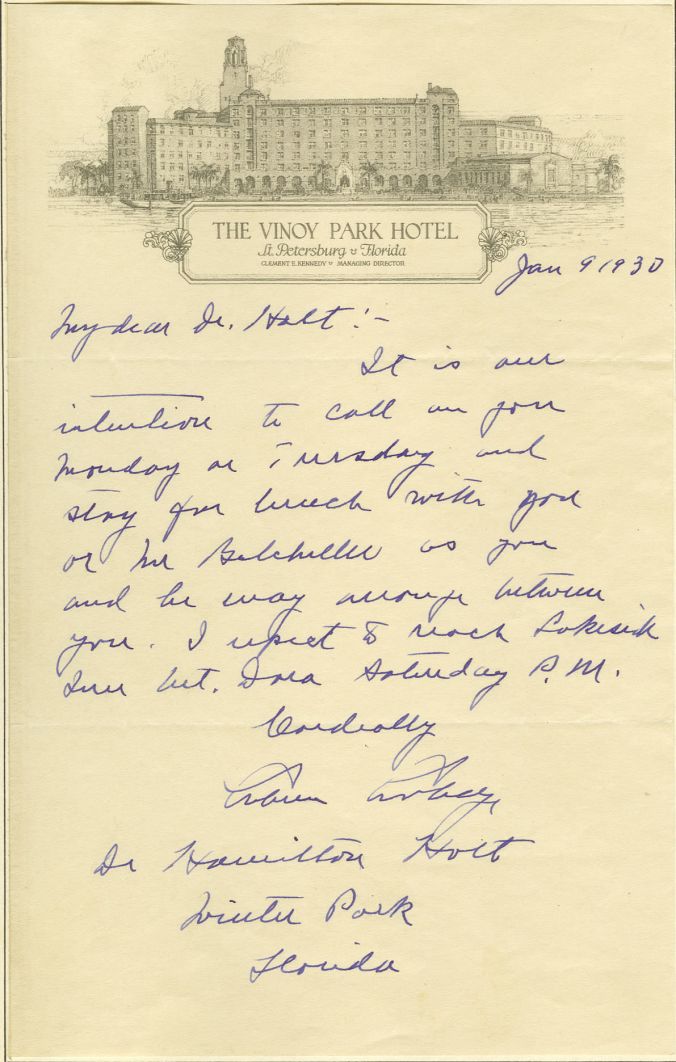

Photo of Coolidge and his Cabinet, taken in the winter of 1924. Back Row: Andrew Mellon, Treasury; Harlan Stone, Attorney General; Curtis Wilbur, Navy; Howard Gore, Agriculture; James J. Davis, Labor; Front Row: Charles Evans Hughes, State; John Weeks, War; Harry New, Postmaster General; Hubert Work, Interior; and Herbert Hoover, Commerce. Notice there are three changes in personnel since Coolidge succeeded to the Presidency, replacing Daugherty at the Justice Department, Denby at Navy and Wallace at Agriculture. Lincoln’s portrait hangs above the mantle.

The President sat at the head of the table with the entire Cabinet assembled for the first time on August 14, 1923. The Coolidges, never ones to nurse grudges or harbor retaliation (despite Mrs. Harding’s refusal to accept the donation of a Vice Presidential residence on behalf of the Coolidges), gave the widow time and a full use of White House rooms before moving in themselves in late August. As the Department officers sat around the table they had known for two years, there was much upon which to reflect. There was especially much for which to be appreciative, despite the loss of their great chief. It was indeed fortunate that someone so capable was there to step into the late President’s chair, not only cleaning up the multiple messes inherited but building on the work begun by Harding. Applying greater resolve, consistency and substance than anyone around that table initially anticipated, Coolidge, fully in command, would present his expectations for how things would operate in the days and months ahead.

Enthusiasm gave way to sober introspection as one man proposed a cheer for new President Coolidge only to be firmly shut down by the others. The other Department heads quickly responded that this was not the time for effusion but silence, especially with Mrs. Harding still in the White House. It was at such a remark that the new President replied with what would prove to be the first of many dry retorts. It was precisely the time to laugh a little before returning to the work awaiting everyone. Coolidge knew that levity served a necessary purpose, especially in the difficult times. He would face some intense opposition in the coming years, but he set the tone at the outset with an effective supply of ready humor and humble self-deprecation. Just as important as laughing at the humor in a situation is being strong enough to laugh at one’s self. Coolidge could do both. The serious and whimsical qualities of his nature were, as Colonel Starling noted, “mixed, so that the one interpenetrated the other.” To Starling, “it seemed a step forward in evolution, for the serious side of life needs to be looked at with the tolerance and understanding which a sense of humor provides, and our laughter should be grounded in an understanding of the spiritual purpose of our existence” (Morris K. Udall, Too Funny to Be President, p. 233).

Charlie Chaplin and Mack Sennett seen together in The Fatal Mallet, 1914. Mabel Normand stands between them.

The thirtieth President, as someone has observed, was “not only the master of the understatement but commander of the punch line” (Sloane, Humor in the White House, p.51). As director Mack Sennett, the original “King of Comedy,” once said, Coolidge was an “expert practitioner” when it came to the art of “deadpan” humor. Coolidge’s brand of comedy consisted not merely of the Vermonter’s grasp of comedic expression but also a “highly developed sense of timing,” as Sloane observes (p.50). Coolidge applied a unshakable seriousness of mind and tenacity to his work that would markedly set him apart from most of his predecessors, especially Harding. Yet, through it all, he also injected a healthy balance of good humor from a deep reservoir of dry wit to lighten burdens, entertain himself and, most importantly, to bring a sense of proportion back to the situation. As Coolidge had learned from his days in Massachusetts and throughout those first few years under President Harding, Washington needed perspective then as it does now, an ample dose of truthful insight combined with a readiness to make light of the absurd, even when the source of that absurdity is policy, Parties, politicians or the President himself.