Thirteen-year-old Harry Blaney had been working on a gift for the President and First Lady, staying that summer (the Coolidges’ first since losing their youngest boy to septicemia the previous July) at “White Court” in Swampscott, the large oceanfront house just six miles away. Blaney, whose family lived in Lynn, was the oldest boy of three, and the second oldest of Harry Sr. and Lillian Blaney. His father’s company, the Preble Toe Box Factory, made imitation leather toe boxes, the ‘box’ accommodating the space needed for toes in closed-toe shoes. The Blaney family worked hard, and young Harry aspired to follow in the family trade. On Thursday, July 2, 1925, just ahead of the President’s birthday weekend, Harry’s project was completed. He would be brave and deliver it himself. Harry had carved a wooden figure of the President, Mrs. Coolidge, and their dog, Rob Roy. His best chance to deliver his gift directly required that Harry leave the family residence on Groveland Street in Lynn bright and early in the morning to reach Littles Point in Swampscott, before the President began his workday. It might be seen as a presumptuous imposition but what young Harry had to give was important and worth crossing what perhaps was the smallest distance he had ever been (or perhaps ever would be) from a President. Moreover, as he recalled, the President had lost a son just a little older than himself. Harry would go right up to the gates of the residence and wait if had to, confident that someone would appear to accept his gift. He did not have to wait. He met the President out in the neighborhood still on his early morning walk. Mr. Coolidge stopped and spoke with the boy for a few moments but then Harry realized the ideal moment to proffer what he had brought was slipping away. He thrust out the wooden figure and relayed his regards. The President, always affected by sincere gestures of kindness and generosity from boys like Harry, thanked the young man for so kind a sentiment, and they parted.

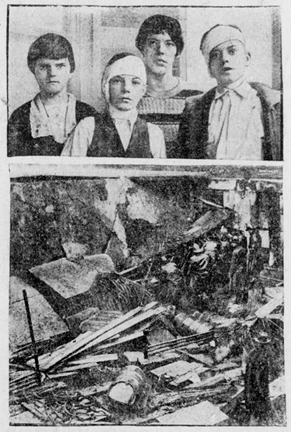

It was another early morning, this time in November, four years later, that now seventeen-year-old Harry prepared to sit down to breakfast with his entire family one last time. The first blast followed swiftly by a second which engulfed the house in flames, set five other homes ablaze, threw employees out windows and doors or through the foot-thick concrete block walls of the factory. The explosion threw the various members of the household in all directions in a tower of fire. Employees were incinerated, blown to pieces, or otherwise suffocated. Others later died of burn injuries in the hospital. The fire departments of all surrounding neighborhoods rushed to the site, finding the scene a roaring, glass-strewn horror. The heroic actions of the fire departments to rescue the trapped, extinguish the flames, and extricate burn victims that day must be combined with the legendary work done by the medical teams at Lynn’s Hospital. Still, it was part of the entire community’s heroism. Some were rescued by quick-thinking bystanders who tore burning clothes from frantic victims fleeing the scene. Others by the twelve-year-old boy who triggered the first alarms by standing atop another’s shoulders. Even a makeshift triage center was set up by a neighbor across the street. Heroic sacrifice mingled with astounding grief. Harry’s mother and five of his siblings, including his six-month old sister, were caught by the blaze in the collapsing rubble, dying almost instantly. Their father, horribly burned, succumbed to his wounds in the hospital ten days after the funeral for their family. Even Harry and his brother Norm, violently thrown by the blast, had serious but non-life-threatening injuries. Twenty-one died as a result of the disaster. Only Harry and Norm, with sisters Lillian and Ella, remained from the Blaney family. In the investigation and inquest that followed authorities traced the origin of the disaster to an ignition of the factory’s highly flammable celluloid (used in the processing of the imitation leather fabricated for toe boxes). The indictments and court proceedings that unfolded afterward initiated fire prevention and zoning regulations for towns like Lynn. Smaller towns and cities permanently separated residential from commercial properties and stipulated long-overdue precautions respecting the storage and handling of combustible materials like celluloid.

A mere five days after the explosion, on November 13, 1928, a letter expressing profound sorrow found its way to young Harry from the President of the United States. Coolidge had not forgotten him or his sentiments that Independence Day week four years prior. “I hope you may find some consolation to relieve the heavy burden of sorrow that has come to you,” the President wrote Harry, “My deep sympathy goes out to you and the members of your family who have survived the shocking tragedy.” Young Harry did survive and found redemption out of the unspeakable loss. The gifts he (and his community) gave, beginning with one to a President a century ago, continue as reminders, however, that we recall greatness not in the act of receiving but in the act of giving. That is what makes the two hundred forty-ninth year since 1776 and one-hundred-fifty-third birthday of Coolidge so meaningful to us. They impart the reminder that redemption through loss remains. Moreover, they connect the gifts bestowed by the Declaration’s Signers with those of a young boy named Harry one hundred years ago.