As President Coolidge stood before the thousands of lobbyists, farmers, ranchers and agricultural professionals gathered in Chicago, it was becoming increasingly evident that this was not what they wanted to hear. The President was answering their plea to Washington for special help with a firm “no.” Moreover, Coolidge was about to launch into a wealth of statistical data in order to counter the central assumption that government had to act to meet emergency conditions. No emergency existed. Coolidge knew that crises were notoriously disastrous environments to properly and carefully consider drastic legislation, whether it be for farmers, veterans or anyone else. Contrived calamities advance the interests of bureaucrats and lobbyists not the welfare of all the people.

American farmers were experiencing real improvement after the low point of 1921. General trends since 1900 were slowly, but surely, beginning to reach farm prices. Neither the Congress nor his Administration could accelerate that process so that market demand could be supplied to compensate for overproduction. Coolidge was not blindly proclaiming a return of pre-war levels of prosperity either. Such levels were beyond anyone’s reach now. The market furnished the only true value of what farmers had hastily overproduced. No partnership of government and corporate entities could neatly raise the value of one product to keep returns high and costs low, especially when the markets knew otherwise. Advocates of a government rescue seemed to feel that America was still stuck in 1921 and it was the responsibility of government and business to remove the consequences of poor decision-making on the part of farmers. Farming was hard enough, they claimed. It was for no lack of sympathy nor a denial of reality that Coolidge stuck to his guns and refused to succumb to the pressure that “crisis” compelled another unnecessary raid on the Public Treasury.

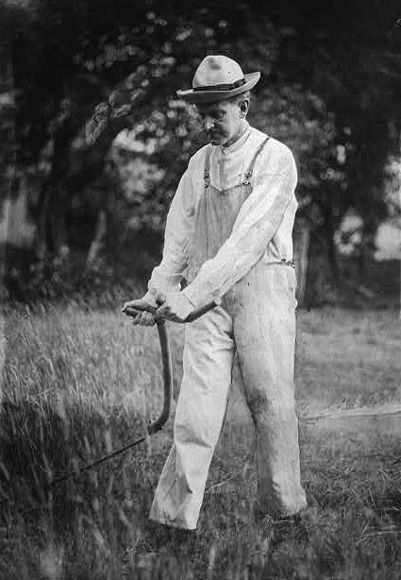

Former President at his Vermont family farm. He and his horse are ready to put the hay baler to work, July 1931.

The advocates of government relief did not want to be bothered with the facts, though. This did not deter Coolidge from affirming what trends actually revealed: while rural populations were decreasing, production was going up. In fact, production had grown fifteen percent since 1910, a remarkable reality given that the economy had experienced four years of war, an economic depression and witnessed the move from a rural to predominantly urban population. “Fewer people but more production means each person on the farm will receive more.”

Production was but one part of the equation, Coolidge went on to say. Prices were at the heart of the controversy. However, prices were also going back up. No, they were not yet to where they had been before the war. Nothing, for that matter, was at it had been. When compared over a quarter of a century, though, what farmers were making had more than tripled to over $12 billion what sold for $3.5 billion in 1900. Farmers had seen a 350% increase in just two decades! Of course, commodities all across the spectrum had increased in value and the decline of 1921 hit hard, but purchasing power had exceeded even those hits to its worth. Agriculture was not in crisis. Depressed areas could be found, just as debt and taxes continued to burden farmers as well. President Coolidge, who knew directly what it was to struggle on the farm, reminded his audience that these were indicators not of permanent decline but demonstrated that agriculture was improving.

What medicine to administer depended on the condition of the patient. Farming was neither on a deathbed nor stricken in a sick room. Agriculture was rallying back toward full health. It was not there yet but the treatment, if given by government, would prove worse than the cure, Coolidge maintained. Even were the medicine coated in the garb of corporate partnership with government, experience taught President Coolidge how “dangerous” and destructive it would be to the freedom of the market. “No matter how it is disguised, the moment the Government engages in buying and selling, by that act it is fixing prices. Moreover, it would apparently destroy cooperative associations and all other market machinery, for no one can compete with the Government. Ultimately it would end the independence which the farmers of this country enjoy as a result of centuries of struggle and prevent the exercise of their own judgment and control in cultivating their land and marketing their produce.”

The President knew that however rationalized the government’s “alternative choice” is advertised, the result is always a removal of competition and establishment of one, sole provider — the Federal Government, forcing Americans to pay whatever it decides, however high or artificial a price. The costs are not merely economic ones, either. “Government control can not be divorced from political control.” The project may start innocently enough by insulating producers from low prices and bolstering superficially high values on what is sold. The agricultural policies of other nations, Coolidge pointed out, reveal that price fixing, once entrusted to government, cuts both ways. One of Europe’s great nations had already capped the price of farm labor far below what it was worth. America, were it to set out on that same course, would soon find that a government empowered to give can also take away.

Coolidge also understood that no government has the ability, even with “the best and the brightest,” to surgically adjust one price without seriously influencing all the other costs and components simultaneously operating in the market. The only way to prevent this ripple effect invariably led to the wholesale takeover of the economy by government. American agriculture would no longer be American. Government could not manage one small piece without assuming management of it all to ensure desired results for any length of time. “Unless we fix corresponding prices for other commodities, a high fixed price for agriculture would simply stimulate overproduction that would end in complete collapse.” Farmers realized, Coolidge asserted, “that even the United States Government is not strong enough, either directly or indirectly, to fix prices which would constantly guarantee success. They are opposed to submitting themselves to the control of a great Government bureaucracy. They prefer the sound policy of maintaining their freedom and their initiative as individuals, or to limit them only as they voluntarily form group associations. They do not wish to put the Government into the farming business.”

If Government price fixing was not the answer, what other option would address the farmer’s plight? The President turned to a discussion of tariff policy. Coolidge delved not into emotional rhetoric, anecdotal evidence or political pandering to accentuate the unfair deal foisted on the farmer. Instead, he cited the figures and invited everyone to “fact-check” him. If it was discovered that the tariff carried a disproportionate burden on agriculture, it needed to change.

If, however, upon examining the numbers, farmers obtained a high wall of protection from the costs of imported goods, the argument to change fell flat indeed. The facts confirmed that 88 percent of imported goods enter the country free of duty, are luxury items the farmer does not purchase or are paid by industry and commerce on behalf of the farmer. The vast majority, some eighty percent of what is imported free of duty, consists of agricultural goods. This leaves the farmer to pay a maximum of 12 percent for goods he never uses while the other sectors of business pay 36 percent on items “which do not benefit them.” The quantity paid by the farmer decreases even further when the actual expenditures of the average farm household are taken into account. In reality, a mere 1.3 percent of tariff costs falls to the farmer. If anyone is being disproportionately charged under tariff policy, it is anyone but the farmer.

Protection, more than a neutral policy yielded a positive good to agriculture. By exacting costs from foreign products, both the volume of imports and their dilution of American purchasing power was curtailed. It was because of the tariff that the standard of living continued, crop diversification was encouraged and home markets were protected. Because of the tariff employment was kept low and wages remained high. Protection for our own products and labor ensured that foreign competition did not supplant quality with quantity and qualified labor with cheap employment at home. Protection protects the farmer, already struggling as it was, to increase not only the strength of the dollar earned but the ability to employ more here at home, reaping the rewards of market prosperity as a whole. As Coolidge would confirm the service of America’s tariff policy unchanged, he declared, “Protection has contributed in our country to making employment plentiful with the highest wages and highest standards of living in the world, which is of inestimable benefit to both our agricultural and industrial population.” There was no need to redo the law making tariffs any more helpful to farmers than it was already proving to be.

As President Coolidge neared the close of his address, he finally offered what he saw as the soundest answers to the “farming problem.” In Part 3 of our overview, “Silent Cal” gives his take on what can be done in agriculture.

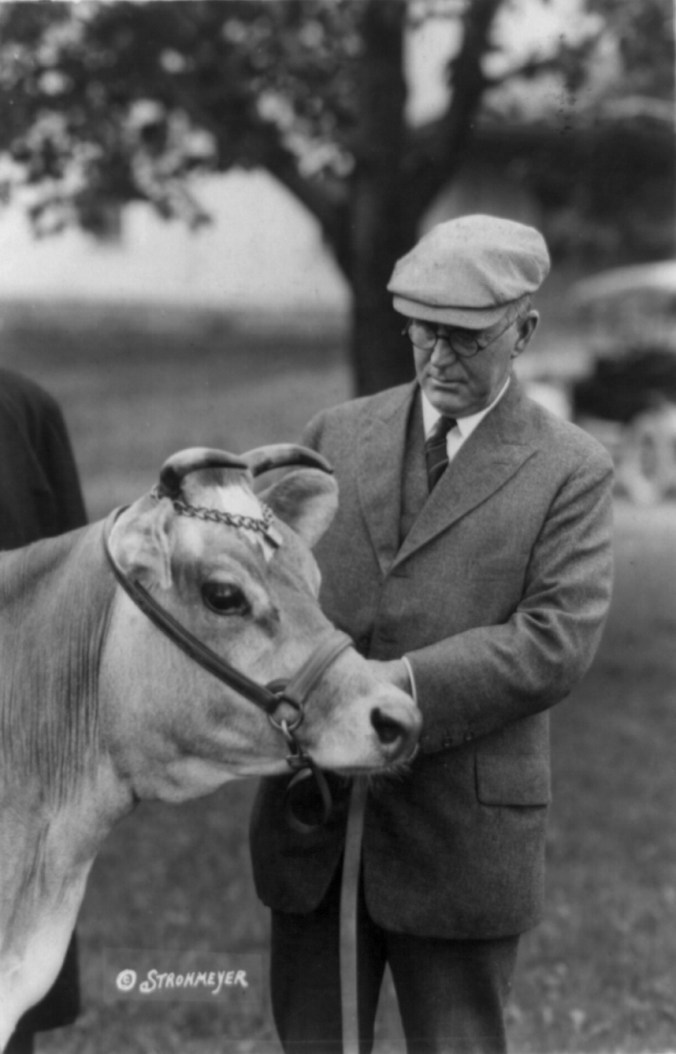

Then-Vice President Coolidge adjusting the gag swivel for one of his horses during work at the Notch, 1920.