Apprehensions over the future have always remained an ever-present concern for a wise and circumspect people. When Americans stop being concerned for the next generation, it will be because we are no longer free individuals. The prospects for freedom stand in greater doubt than perhaps they have for many years, but a lack of confidence in our system is only new to us, not to generations of Americans who came before us.

Any one of the hardships overcome by prior generations could have halted the experiment of self-government in its tracks. It has certainly had no shortage of critics who proclaimed “failure” and “defeat” only to be proven flatly wrong time and time again. Inequity and unfairness have been present in human history from the outset, but neither has had the power to prevent individuals of determination from accomplishing truly great things despite it. Our time is hardly the first to ask, “who is worthy of freedom?”

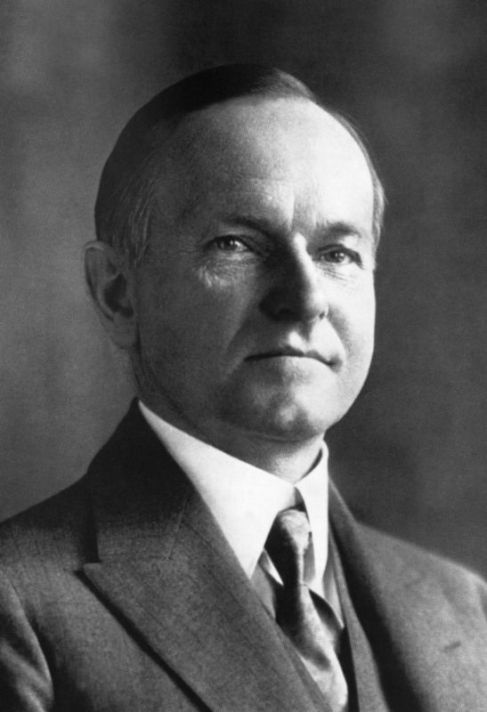

The Progressive Era produced an almost overwhelming array of reasons to change the way this country was established. It would answer our question with pessimism: the people were ultimately not to be trusted with freedom. It was an intelligent few who merited such power. Coolidge knew, on the other hand, freedom was safest in the hands of the people.

The charge that our system was both too wild and too unequal, compared to the “enlightened” societies of Europe, led to calls for regulation of human behavior on a scale never before known. The pursuit began to implement an efficient and intelligent approach to government that would mitigate risk, remove inequities and shepherd the people to progress.

These activists, predisposed to intense skepticism about capitalist systems, trusted government implicitly with greater and greater control. Enamored with a lopsided admiration for methods foreign to American ideals of law and liberty, these generally middle class intellectuals failed to appreciate the remarkable nature of our constitutional system. They overlooked the careful balance worked out by the Framers, infusing a disastrous measure of good intentions with a reckless accumulation of new laws.

They entrusted government with the power to supply the shortfalls of human nature with legislation. Each effort undervalued, even ignored, the unquantifiable worth of freedom. Government, endeavoring to be “smart” and “humane,” hurt those it proclaimed to help by robbing them of the dignity of free will, the moral judgment of those given sovereignty in our system.

Ours is a history of accomplishment and success because people were recognized not as subjects in service to the State but individuals whose value comes from a Divine Creator. Made in the image of God, it logically follows that the dreams, aspirations and abilities to create, construct and succeed are within every person’s power. It is that power now being denied our young people as unrealistic and unattainable. This is nothing more than the latest incarnation of those who denied Edison could harness light, the Wrights could fly and Ford could mobilize America.

The avoidable tragedy of all this is that it literally destroys the wholesome yearnings of millions for something better than marginal existence. Instead, the young are told to be content with mediocrity, cease the pursuit of success, and consign all future faith and hopes to Washington’s management. No less self-deluded than the Progressives of Coolidge’s day, this operation dehumanizes humanity. History proclaims it will ultimately fail but the cost to countless lives in the process can never be known.

Coolidge, grappling with these problems, said in 1923,

[T}he motive power of progress and reform has not come from the high and mighty but from the mass of the people…It is not the quantity of knowledge that is the chief glory of man…It is in the moral power to know the truth and respond to it, to resist evil and hold to that which is good, that is to be found the real dignity and worth, the chief strength, the chief greatness. This power, even in the humblest and the most unlettered, rises to a height which cannot be measured, which cannot be analyzed. It is this strength of the people which can never be ignored. Of course it would be folly to argue that the people cannot make political mistakes. They can and do make grave mistakes. They know it; they pay the penalty. But compared with the mistakes which have been made by every kind of autocracy they are unimportant…

…Unless the people struggle to help themselves, no one else will or can help them. It is out of such struggle that there comes the strongest evidence of their true independence and nobility, and there is struck off a rough and incomplete economic justice, and there develops a strong and rugged national character. It represents a spirit for which there could be no substitute. It justifies the claim that they are worthy to be free…

…Civilization and freedom have come because they are an achievement, and it is human nature to achieve. Nothing else gives any permanent satisfaction. But most of all there is need of religion. From that source alone came freedom. Nothing else touches the soul of man. Nothing else justifies faith in the people.

Like the generation who saw beyond the narrow confines of subsistence imposed upon it by king and Parliament, it is time to refuse to participate in a supervised decline. Being taught to doubt our own judgment is merely a prelude to forfeiting the ability to make our own choices, to strive, to fail, to triumph — in short, to live free. If we are to be worthy of that freedom, we cannot surrender to this latest effort — however organized it is — to train out the moral ideals and intangible dreams of people.