Calvin Coolidge, writing his column after the midterm elections of 1930 were known on November 4 of that year, observed, “Some people will be disappointed and some will be elated. But there will be enough representatives of different parties holding office during the next two years so that no very violent change in policy will be made…We make our own government. If we fail it is our own fault. Under our system a nation of good citizens cannot have a bad government.” The keyword for Mr. Coolidge was good. If citizens are doing what they are supposed to do — exercising their responsibilities seriously — no bad government would stand a chance of being elected. As he would say at other times, “government is what we make it.” It was a more profound way of saying elections have consequences. While Coolidge was largely correct that “no very violent change” would take place in the next two years, 1932 would transform everything. Burton Folsom, in New Deal or Raw Deal?, and Amity Shlaes, in The Forgotten Man, document the upheaval in domestic policy with the election and inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Foreign policy was no less submitted to drastic overhaul. Three instances illustrate this point.

First, the “Good Neighbor Policy” of “religious adherence” (as Cordell Hull, Roosevelt’s Secretary of State, would describe it in his Memoirs, p. 310) to nonintervention enabled ambitious and unscrupulous men to overthrow their native institutions and establish dictatorships, like the Somozas in Nicaragua. Preceding administrations, including the policy of President Coolidge, did not take American involvement off the table. Coolidge recognized that America possessed great moral responsibilities to others, especially in our hemisphere through the Monroe Doctrine. It was not justification for involvement in every dispute to come down the pike, as in Wilson’s call to make the world safe for democracy, but if her citizens were not defended and law and order not respected, especially in her backyard, the heritage of government by laws not men would be conceded away. Might would make right after all. The great accomplishment of 1776, shared by the younger republics of Latin America, was too valuable an inheritance to withhold help entirely.

When the Nicaraguan government petitioned for assistance in November 1926, Coolidge would inform Congress that Marines (2nd Battalion, 5th Regiment) were redeployed, landing January 10, 1927. Over the next few months, with reinforcements, the force of 2,000 Marines fought their way through to protect towns and rail lines from further attacks. In March Coolidge dispatched Henry L. Stimson to resolve the situation. In his first two weeks, he devoted his time to learning from all parties what was happening. In a month, by granting the request from both sides of the conflict for America to intervene, peace was renewed. Both sides agreed to allow the current President to finish his term according to law. Their laws also required an election occur in 1928. Stimson and Frank R. McCoy were commissioned to supervise the election, insuring a secret ballot and fair proceedings. By reaffirming law and administering medical help to those harmed in the conflict, Americans left the country on peaceful terms with only Sandino refusing to lay down arms.

Henry L. Stimson, Coolidge’s representative to Nicaragua, 1927.

The last Marines were withdrawn in January 1933 after the election of Sacasa. It was in March of that year that conditions began to descend again. With the commitment not to intervene determined by the “Good Neighbor” Policy, there was little U.S. Minister Arthur Lane could do as Somoza would kill Sandino the following year and solidify his power by 1936.

Cordell Hull, Secretary of State to Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-1944)

Second, the commitment to nonintervention accepted the false premise of Argentina. When the diplomatic delegations of twenty Latin American countries met in Havana with the United States delegation led by Charles Evans Hughes in 1928, their instructions explicitly included the refusal of nonintervention. That point was not negotiable. The tension in the air was felt by all. President Coolidge would come down to speak, commending respect for law and pursuit of peaceful means of resolution between sister nations.

The next day, however, with the President gone, the simmering conflict boiled over in conference. Argentina was displeased that their beef, failing sanitary standards for importation, was being turned away by the United States. Citing the premise that America was improperly involved in Nicaragua, Mexico and Chile, however, combined with the past year of “anti-imperialist” sentiment, nonintervention came to the floor. The Argentine delegation led the way with the resolution, “No state has the right to intervene in the internal affairs of another.” A flurry of chaotic cheers, cries and rhetoric followed. The Americans, trying to avoid confrontation, sat increasingly apprehensive until Chairman Hughes stood to speak. The room went silent. Hughes began by reviewing the discussion of nonintervention in committee, the agreement that it would be discussed at the next Conference five years in the future, then laid out directly the reasons for each “intervention” in Latin America. While these were discussions best reserved between the U.S. and each nation concerned, Hughes methodically outlined the requests for intervention, the help provided by Americans and the threats to life and property when respect for law is discarded.

Charles Evans Hughes, Secretary of State under both Harding and Coolidge (1921-1925), who came out of private life to lead the American delegation at the Pan-American Conference in Havana, Cuba, 1928.

As he finished, he appealed,

“I am too proud of my country to stand before you as in any way suggesting a defense of aggression or of assault upon the sovereignty or independence of any State. I stand before you to tell you we unite with you in the aspiration for complete sovereignty and the realization of complete independence.

“I stand here with you ready to cooperate in every way in establishing the ideals of justice by institutions in every land which will promote fairness of dealing between man and man and nation and nation.

“I cannot sacrifice the rights of my country but I will join with you in declaring the law. I will try to help you in coming to a just conclusion as to the law, but it must be the law of justice infused with the spirit which has given us from the days of [Hugo] Grotius this wonderful development of the law of nations, by which we find ourselves bound.”

The room sounded with applause from every delegation. Support for the resolution evaporated and the Conference closed with a better understanding between nations. By removing intervention entirely from United States’ relations in Latin America, the “Good Neighbor” Policy (adopted from 1933 onward) accepted the short-sighted premise that had been refuted by Hughes so powerfully five years before. It demonstrated that elections can change the world and not necessarily for the better, when it hamstrings the protection of lives, possessions and law.

Third, the commitment to withhold recognition of the Soviet Union was abandoned without meeting America’s longstanding criteria. Since the Revolution of 1917, the United States (through Presidents Wilson, Harding, Coolidge and Hoover) had withheld official recognition from the new communist regime. As long as Moscow funded, trained and encouraged activities that subverted our institutions, our laws and our government, the Coolidge administration would continue to refuse recognition. The revolutionaries, in confiscating properties owned by Americans living in Russia as well as failing to repay debts owed to the United States, the Soviet Union would not be received. Such were the requirements the United States required for sixteen years, until 1933, when the simple promise to stop interfering, either overtly or covertly, in the “internal affairs” of the United States, its citizens and its possessions, was accepted by the Roosevelt administration. While, as Hughes noted in 1944, “All the aims of Stalin’s diplomacy” were “not yet fully known,” the Venona Transcripts and seventy plus years of subterfuge and violence reveal what the regime was enabled to accomplish thanks to this official recognition of “Uncle Joe” Stalin’s regime.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and “Uncle Joe” Stalin, meeting at Yalta in February 1945.

These are all reminders that good intentions alone do not make good policy. The mistakes of each administration are not only felt at home but around the world. A fundamental strength of the Coolidge era policy rested on the preeminent importance of law and order. The law presides over us all, in conflict and in peacetime alike. If we disrespect that law and turn away when our neighbors call for our aid, how is the principle of might does not make right discredited? By abandoning neighbors to ambitious and violent people who flout the law, how is the policy of nonintervention, at the expense of law and order, helping anyone?

The Coolidge administration reaffirmed the Monroe Doctrine in this hemisphere. It was not a universal call to police the world. It was a call to adhere to government by law and order. In contrast, Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor” Policy was a plan intended for every continent. The removal of American leadership from the world scene articulated by this posture did more to encourage the storms of the twentieth century than anyone could have possibly intended.

Under Coolidge, we deferred to the authority of the sovereign nations of Europe to govern their own sphere. It is what independent nations do. As Coolidge understood well, every benefit carried with it an equal responsibility. The responsibility of Europe was to meet their obligations from the war and rebuild free and peaceful nations in their sphere. Shirking that obligation is how the matter of war debts and reparations became a burden largely assumed by the United States instead of responsibly paying it back as promised. Like the League of Nations did with Mussolini in 1935 and Hitler in 1938, however, Europe found it generally easier to shift their responsibilities to American shoulders. By placing constitutional law and orderly liberty as secondary to nonintervention, the Roosevelt administration illustrates the heavy costs of bad citizenship. Good policy starts with good citizens.

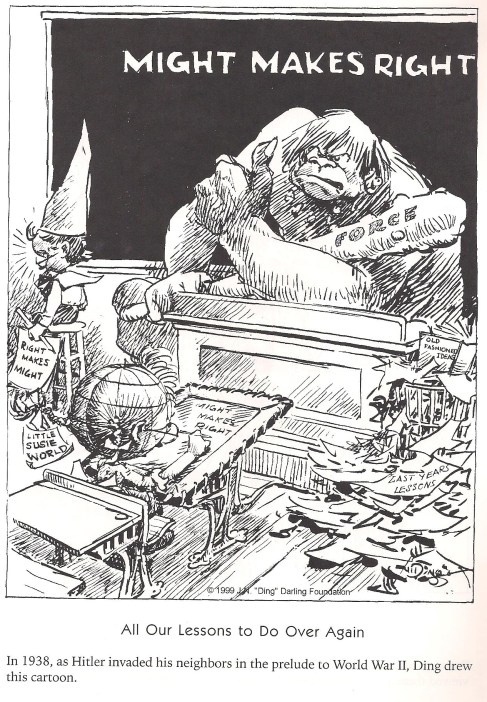

Ironically, “Ding” Darling had been skeptical of Coolidge’s policy of intervention in Latin America. Cartoon published in A Ding Darling Sampler: The Editorial Cartoons of Jay N. Darling. Mt. Pleasant, SC: Maecenas Press, 2004.

References

Bemis, Samuel Flagg. The Latin-American Policy of the United States: An Historical Interpretation. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1967. pp. 242-255.

Hughes, Charles Evans. The Autobiographical Notes. Eds. David J. Danelski and Joseph S. Tulchin. Cambridge: Harvard, 1973. pp.261-279.

Hull, Cordell. The Memoirs of Cordell Hull. 2 vols. New York: Macmillan, 1948. pp.292-351.

Stimson, Henry L. American Policy in Nicaragua. Princeton: Markus Weiner, 1991.

Stimson and McGeorge Bundy. On Active Service in Peace and War. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1948. pp.111-116.