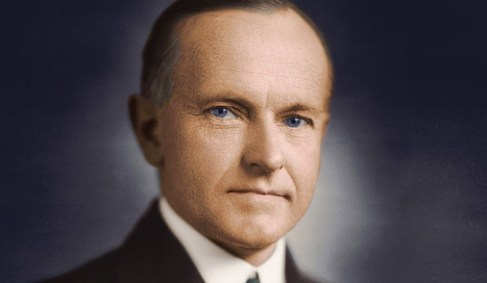

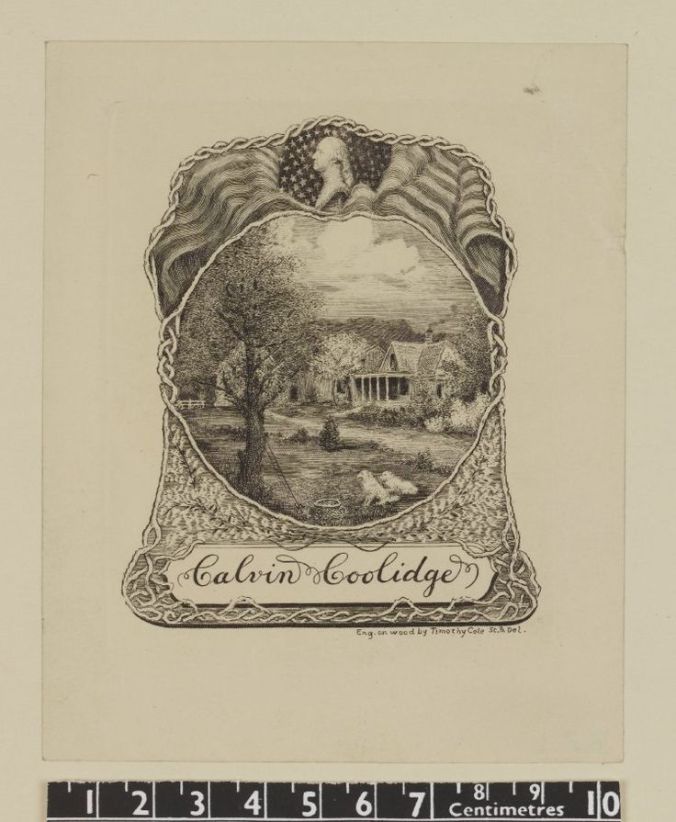

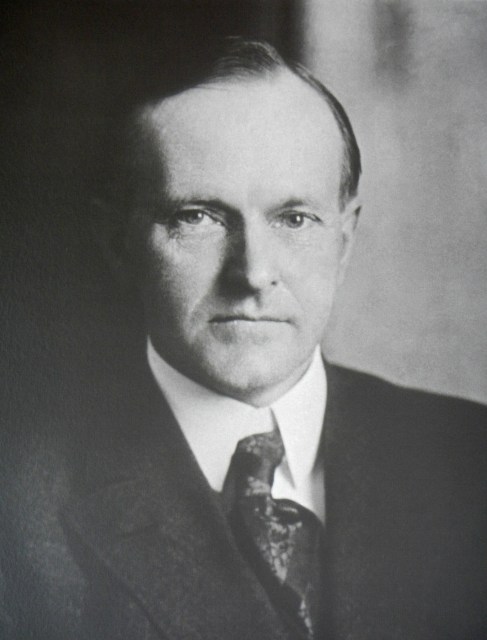

In all the discussion over the years concerning the deficiencies of modern education, from the improvement of testing standards, the adoption of new curricula, or even the construction of expansive facilities, the most fundamental component is missing. The purpose of education, for most of America’s existence, has been encouraging the student’s grasp of morality and sense of service to others. So it was for the last classically educated President in our history, Calvin Coolidge.

For all the concern over school shootings, sexual misconduct, drugs, violent outbursts, and other self-destructive behavior, the basics continue to be neglected as incapable of addressing the “complexity” of the issues. This is a refusal to live in reality. It is a decided effort to run from the hard decisions of maturity, allowing immature and unhealthy impulses to dictate both the lives of individuals and the governance of schools.

No one is born with perfect behavior, impeccable manners, or maturity. These qualities must be taught, for students absorb both the good and the bad. Cut out the moral core and there is no compass to help the individual discern good from evil values. Moreover, the young are no longer taught the most basic virtues of character: self-control, temperance, kindness, forbearance, patience, charity, and diligence. Instead, moral instruction is ridiculed as an attempt to impose extreme codes of behavior or to establish a state religion. Animalistic behavior is regarded as normal, and any attempt to reaffirm essential standards of conduct is met with organized ostracism from accepted society by politically correct elites. In truth, character has nothing to do with a “separation of church and state” and everything to do with a good and healthy civilization.

We are failing our children egregiously. The individual is treated as mere biological matter or, at best, mind without conscience, free to respond to any and every stimuli while simultaneously being devoid of a spiritual nature or the needs of the soul. Mere relay of information is not education. Transmitting data, shorn of any idea that truth exists and can be known objectively, does not fulfill a teacher’s obligation.

Coolidge said it best,

“Man is far more than intelligence. It is not only what men know but what they are disposed to do with that which they know that will determine the rise and fall of civilization…The realization of progress that has marked the history of the race, the overwhelming and irresistible power which human nature possesses to resist that which is evil and respond to that which is good, are a sufficient warrant for optimism. If this were not so, teaching would be a vain and useless thing, an ornament to be secured by a few, but useless to the multitude.”

Coolidge thought such a narrow base of informed and truly educated people was not right. Proper education reached as many as it could. Proper education did not abandon certain communities, specific demographics, or particular economic strata. It seems some today have surrendered the standards because too few live up to them. Hence, literacy continues to fall, historical awareness evaporates, and nothing is required of the inmates running the asylum.

Coolidge appealed to higher standards proven by decades of historical experience. People were not richer, wiser, better, or purer than they are now, but they knew the effort to aspire to standards was worth it. Aspiring to the ideal — a character formed and maintained through constant effort — was worthy not because perfection could be realized, but because good character is found in its pursuit.

Coolidge continues,

“Our country…has founded its institutions not on the weakness but on the strength of mankind. It undertakes to educate the individual because it knows his worth. It relies on him for support because it realizes his power…[T]he chief end of it all, the teaching of how to think and how to live, must never be forgotten.

All this points to the same conclusion, the necessity of a foundation of liberal culture, and the requirement for broadening and increasing the amount of moral intellectual training to meet the increasing needs of a complicated civilization. Free schools and compulsory attendance are a new experience. No power of government can bring them to success. If they succeed, it will be through the genuine effort and support that can come only from the heart of the people themselves. It is this condition that makes the position of the teacher rise to such high importance.”

Without the moral and the spiritual to support and sustain the individual, all the “facts” and material stimuli of modernity will leave the student empty, ill-equipped for the potential life holds. It will squander the great inheritance due the next generation: the wisdom of those who thought great thoughts and did great deeds before us.