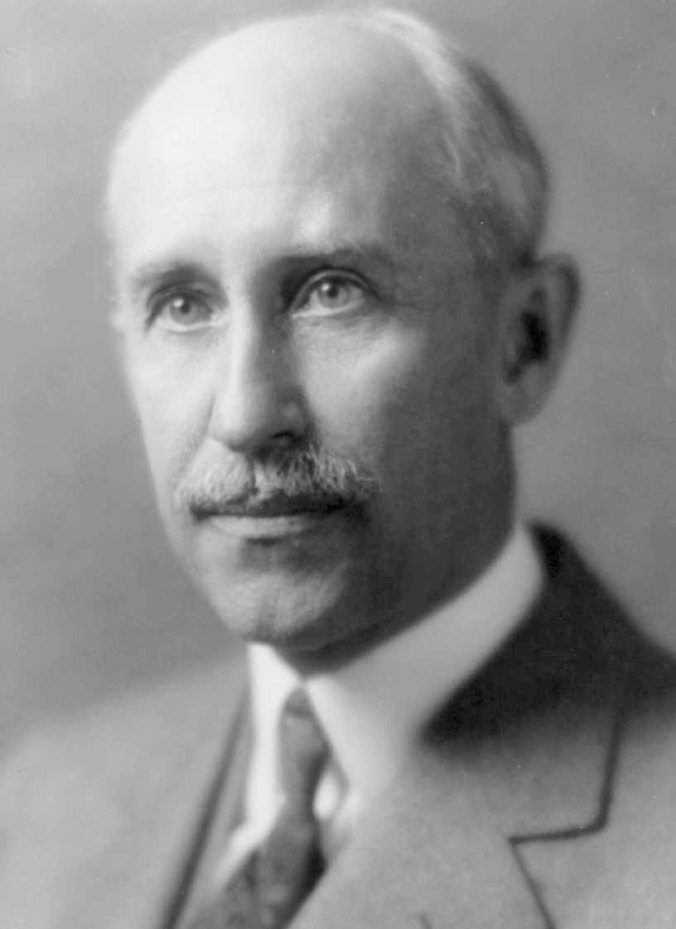

It is an unfortunate assumption all too often made that reserved people are cold, unfeeling and lack basic kindness. Calvin Coolidge is all too easily lumped in this category because he never conveyed the gregarious, slap-on-the-back, “good ol’ boy” transparency that readily lends itself to be understood by and comfortable to most folks. The real Calvin Coolidge, to those who knew him, was far less the “silent,” non-amiable, even prickly persona he exuded to those who were themselves obtuse or narrow-minded. In truth, Coolidge was an exceptionally kind, thoughtful and generous man. His depth of sentiment for people was genuine. To those closest to him, Coolidge could dominate a conversation when the subject caught his interest and his interests were surprisingly broad.

It is an unfortunate assumption all too often made that reserved people are cold, unfeeling and lack basic kindness. Calvin Coolidge is all too easily lumped in this category because he never conveyed the gregarious, slap-on-the-back, “good ol’ boy” transparency that readily lends itself to be understood by and comfortable to most folks. The real Calvin Coolidge, to those who knew him, was far less the “silent,” non-amiable, even prickly persona he exuded to those who were themselves obtuse or narrow-minded. In truth, Coolidge was an exceptionally kind, thoughtful and generous man. His depth of sentiment for people was genuine. To those closest to him, Coolidge could dominate a conversation when the subject caught his interest and his interests were surprisingly broad.

A diligent and devoted Director on the New York Life Insurance Board, Calvin Coolidge rarely missed a meeting and truly invested himself in service to people as he worked. “Mr. Coolidge was a gracious and genial mixer,” his good friend, Thomas A. Buckner once wrote. Arriving early to the latest meeting of the Board, Coolidge took his seat beside Mr. Buckner. A moment later brought a photographer, who asked permission to take their picture. As he prepared for the camera, Coolidge placed his inexpensive, time-worn hat on the stone coping beside him and went on talking. While they waited for the photographer, the room began filling with agents, managers and Directors each piling their hats atop Mr. Coolidge’s. Anxiously seeing the tired old hat he had worn for so many years quickly buried by all the others, he could not sit still any longer. He “darted for the pile” and retrieved it, quickly returning to his seat beside Mr. Buckner.

“I might have lost it. It’s valuable,” the former President said with a twinkle in his eye, holding the tired hat sentimentally just as the photographer snapped their picture. Both men, caught grinning at the remark, took joy in the humor — and sentiment — of the moment. Yet, as Mr. Buckner knew, Calvin Coolidge exemplified more than a feeling for old, familiar things, he cherished people. He manifested a constant and sincere compassion even for those he had never met.

Mr. Buckner explains it best,

“Those of us who came near to Mr. Coolidge knew that his reserve and taciturnity covered a generous nature which might otherwise have been imposed upon by self-seekers. He was always willing to lend a helping hand to others, no matter how humble…[O]ne day Mr. Coolidge entered our home office carrying an enormous bundle. He explained that young man from Newark would call for it and that it would be returned a month hence, at which time Mr. Coolidge would pick it up. The size of the bundle,” Mr. Buckner continued, provoked the curiosity of the secretary, who “asked Mr. Coolidge what it contained.

“He explained that an ambitious young man had entered a contest for window displays, and that he had asked for something from the old Vermont farm. Although the young man did not know Mr. Coolidge personally, his enterprise evidently carried a strong appeal. Mr. Coolidge had therefore carried to New York and generously loaned a bed quilt made by his grandmother many years ago.”

Of all the objects on the farm to give away with the risk of damage, loss or outright theft, Mr. Coolidge could have presented a meaningless trinket devoid of personal or family meaning. As Grace discovered, Coolidge had sewn his own quilt at age ten from whatever material he could scrounge from around the house. Perhaps it was all inspired by his grandmother’s work. Either way, he prized the results produced by his family’s loving hands. He could have chosen some much smaller, far less significant object to grant the young man’s request. He simply did not do that. Instead, he willingly bestowed an item of irreplaceable value: the precious handiwork of grandmother Coolidge. Moreover, he brought it down from the remote countryside of Plymouth to a place infinitely more convenient to this complete stranger than it was for him. He was merely helping someone in what way he could.

“Calvin Coolidge had a deep love for humanity. He is greatly missed, but his spirit remains with us” (Thomas A. Buckner, “Why Director Coolidge Carried a Quilt,” Good Housekeeping, April 1935, p.206).