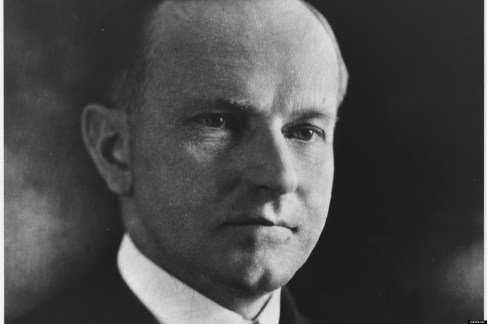

Historian Paul Johnson

It is fitting that those who helped drive the Reagan Revolution forward humbly credit their inspiration to the shy, quiet man from Vermont, Calvin Coolidge. In a very real way he bequeathed the essential recipe for the successes of the 1980s. While the ingredients were not precisely followed in every respect, especially concerning the payment of debt, the principles contained such power that even Congressional spending could not slow it down.

President Reagan’s combination of political saavy, biting wit, unassuming competence and ability to cut through the complex and see the simple essence of an issue derived not merely from his life’s experiences, they found inspiration from his study of Coolidge. Reagan, after all, like several of the men and women who comprised his team of “revolutionaries,” first came to understand the world during the Coolidge Era and in the years shortly thereafter. The lessons “Silent Cal” taught in both word and action left abiding impressions on future Secretaries of the Treasury (Donald T. Regan) and Defense (Caspar Weinberger) and future Attorney General Edwin Meese III, along with many others.

Two scholars, in particular, were returning to Coolidge’s record in order to reassess his very real achievements. In 1982, Thomas B. Silver, in Coolidge and the Historians, would lead this effort and unearth most of the shoddy and partisan reporting against the thirtieth president and the 1920s. In 1984, Paul Johnson, in the sixth chapter of his Modern Times: The World from the Twenties to the Nineties, would roll back the shroud thrown over not only the genuine triumphs of the Roaring Twenties but also the legacy of Mr. Coolidge. As Mr. Johnson would reflect on this reserved and disciplined leader, he would not only find him to be “the most internally consistent and single-minded of modern American presidents” but he, like all of history’s great men, was not an intellectual. To Mr. Johnson, that is a very good thing because “[a]n intellectual is somebody who thinks ideas are more important than people.” Wilson and Hoover approached the world this way while Coolidge, and Reagan, did not. To Coolidge and Reagan, people were the preeminent focus of their policies. The “smartest ones in the room” miss that all-too-obvious truth. People were genuinely benefited by Coolidge’s leadership.

Johnson could accurately survey the Twenties not as an aberration of gross materialism or empty gains but as an unprecedented prosperity that was both “very widespread and very solid” (p.223). “It was,” Johnson corrects, a prosperity “more widely distributed than had been possible in any community of this size before, and it involved the acquisition, by tens of millions, of the elements of economic security which had hitherto been denied them throughout the whole of history. The growth was spectacular.”

As a direct result of Coolidge prosperity, national income jumped from $59.4 to $87.2 billion in eight years, with real per capita income climbing from $522 to $716. Millions of workers purchased insurance for the first time, a phenomenon of a healthy economy Obama is deliberately ignoring. Savings quadrupled during the decade. Ownership in fifty stocks or more reveals the vast majority were not “the rich,” but housekeepers, clerks, factory workers, merchants, electricians, mechanics and foremen. Union membership plummeted from just over 4 million at the outset of the 1920s to 2.5 million by 1932. As small and large businesses succeeded, people were able to provide holidays with pay, insurance coverage and pensions as well as other benefits, giving substance to Coolidge’s dictum that “large profits mean large payrolls” thereby making “collective action superfluous,” as Johnson observes (p.225). Home ownership skyrocketed to 11 million families by 1924.

Perhaps the most obvious index of prosperity could be seen in automobile ownership. What began as a novelty for just over 1 million Americans in 1914 (with less than 570,000 produced annually) exploded into 26 million owners with over 5.6 million autos produced annually by 1929. Air travel was fast becoming the normal mode for “regular” folks and classes were rapidly dissolving from upward mobility. In 1920 a meager $10 million was spent on radios. By 1929 that figure had surpassed $411 million, which was itself small compared to the $2.4 billion spent on electronic devices as a whole in the Twenties.

These years were not, as some would claim later, removed from an appreciation of the past. The expansion of education is “[p]erhaps the most important single development of the age” (Johnson 225). Spending on education increased four times what it was in 1910, from $426 million to $2.3 billion. But unlike today’s habit of throwing money at the problem, it brought results. Illiteracy actually went down over fifty-percent. A “persistent devotion to the classics,” with David Copperfield at the head of the list, defined the decade. Culture was reaching the homes of those who had once been the least connected Americans through reading clubs, youth orchestras and “historical conservation” movements that would restore sites like Colonial Williamsburg.

“The truth is the Twenties was the most fortunate decade in American history, even more fortunate than the equally prosperous 1950s decade, because in the Twenties the national cohesion brought about by relative affluence, the sudden cultural density and the expressive originality of ‘Americanism’ were new and exciting” (p.226).

The problem, as Mr. Johnson concludes, with the expansion of the Twenties was not that it was “philistine or socially immoral. The trouble was that it was transient. Had it endured, carrying with it in its train the less robust but still (at that time) striving economies of Europe, a global political transformation must have followed which would have rolled back the new forces of totalitarian compulsion, with their ruinous belief in social engineering, and gradually replaced them with a relationship between government and enterprise closer to that which Coolidge outlined…” More of the same policies would have prevented much of what followed in the 1930s and beyond. “[M]odern times would have” indeed “been vastly different and immeasurably happier.” The purpose served by Coolidge “minding his own business,” as he put March 1, 1929, was perhaps more a forecast of his successors than an introspection. If only Hoover had been listening more carefully. The downturn in 1929 would certainly have more closely resembled the depression of 1921 and, with the Harding-Coolidge recipe of “masterful inactivity,” have spared millions of lives the terrible suffering and avoidable loss brought on by Hoover’s spending and Roosevelt’s “New Deal.”