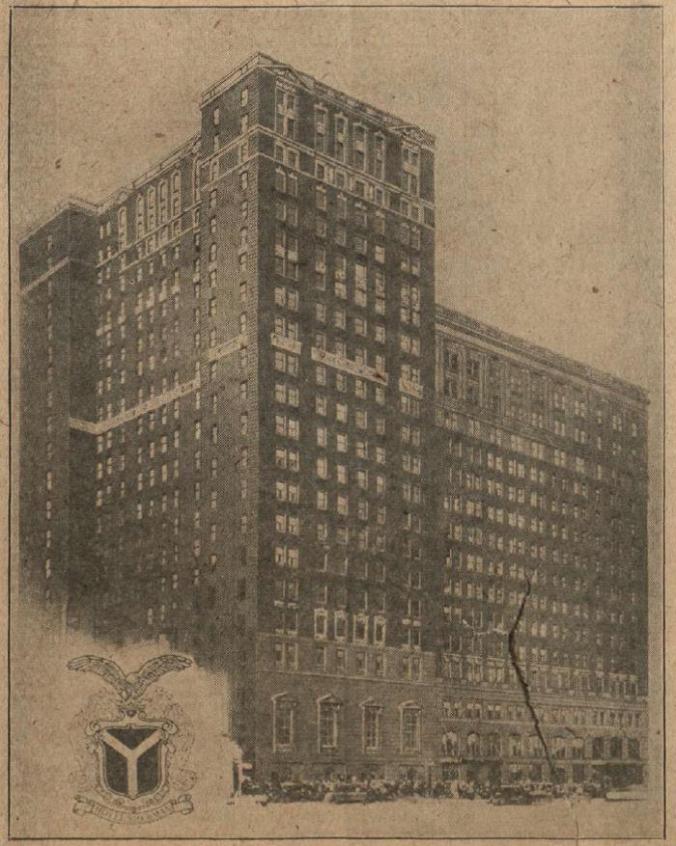

The Sherman Hotel in Chicago where President Coolidge delivered his address on the farmer and the nation, December 7, 1925.

The American Farm Bureau Federation, meeting for its seventh convention in December 1925, had begun five years earlier to accomplish three objectives: (1) extending the terms of credit to allow farmers more time to market what they produce; (2) supporting a high protective tariff which guarded American markets from cheap imports; and (3) advancing a cooperative marketing method for individual farmers to manage ordinary surpluses.

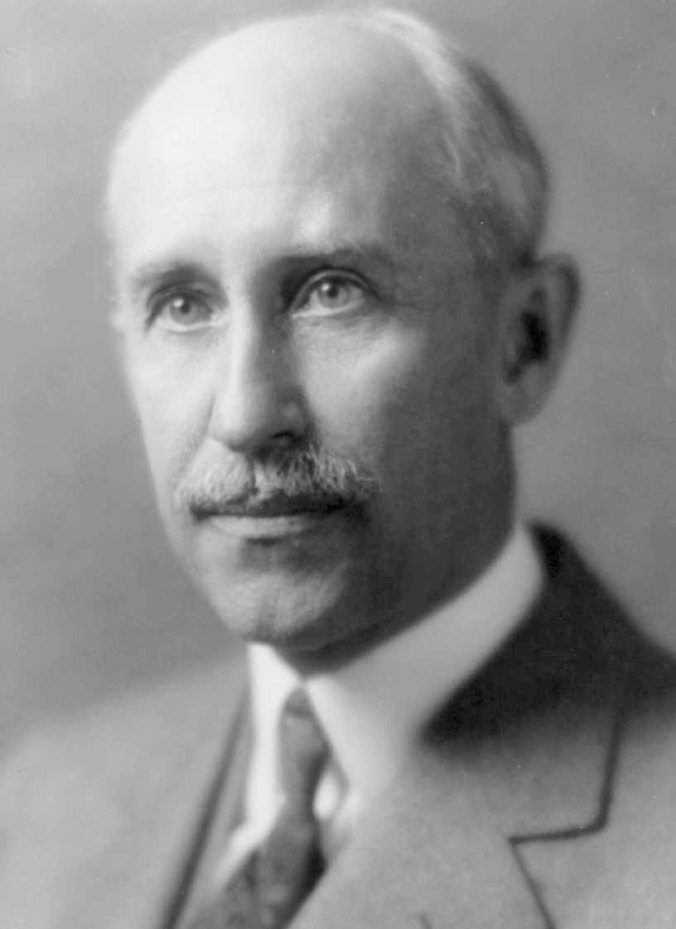

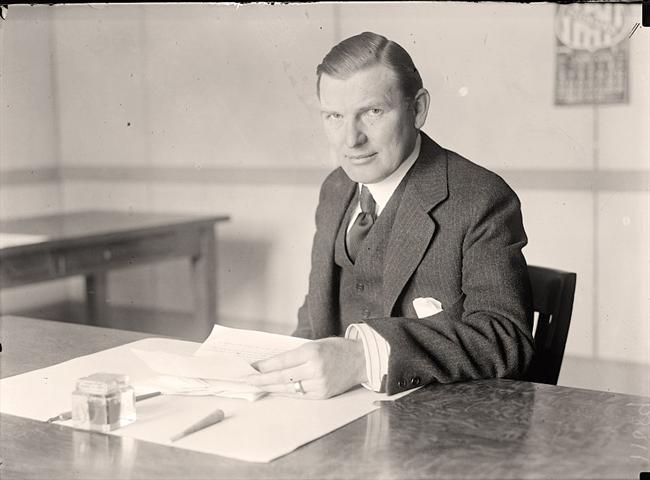

After three years of legislative successes, the Federation chose new leadership in 1922, electing Oscar Bradfute, an Ohio rancher, who took the helm with a commitment to the cooperative approach against the price-fixing program advocated by tireless lobbyist George N. Peek and others. As President Bradfute introduced President Coolidge, he reminded the thousands overflowing the ballroom how important a statement on behalf of agriculture was being made. President Coolidge had traveled two thousand miles to reach the opening day of not merely a Midwestern farm meeting, but downtown Chicago, the headquarters of an organization at the center of all agricultural business. The audience, eager to hear what the President had come so far to say, would find themselves divided in two basic camps after his forty minute address. There were those who wanted immediate results through government price-fixing and those who were confident that America’s farmers, just as Coolidge had said, were best able to emerge on their own from depressed prices, debt and overproduction with the patience, independence and rugged determination that had defined the nation’s farms from the beginning.

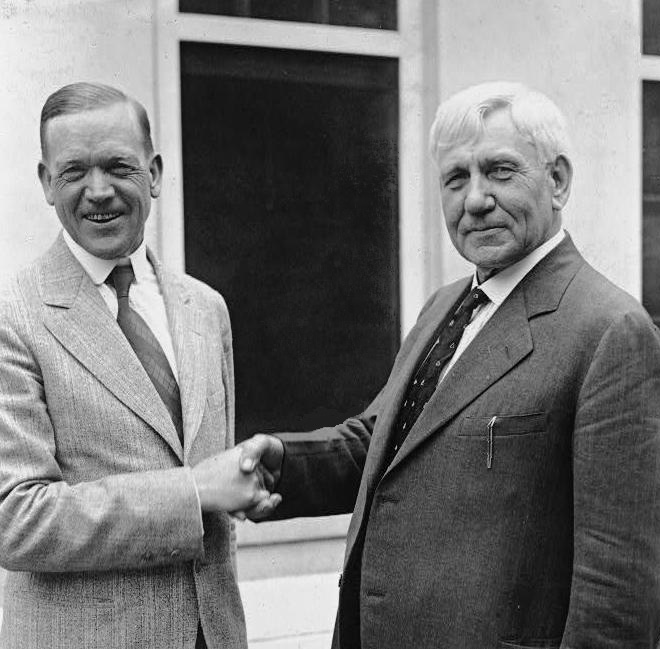

The Coolidges are standing with Oscar Bradfute, to the President’s left, in a picture taken in Chicago before Coolidge’s address.

Government-controlled price-fixing would only harness and undermine the farmer, not improve his circumstances. Changing tariff policy, which already provided immense help to agriculture, would likewise be a step backward not forward. If these would not work, what would, in President Coolidge’s estimation?

First, the President recognized the importance of turning capital loose so that farmers can obtain loans as participants of cooperatives. Cooperatives would cut out the middle men (distributors and marketers) standing between the farmer and the consumer, thereby liberating the transaction of goods with a lowered price and increased profit margin. Of course, distributors and advertisers played a role as well in the market but by freeing up capital and furnishing resources for “sound business advice,” farmers could better help themselves out of agriculture’s preventable difficulties. It was the reason why Coolidge had supported the Norbeck-Burtness bill in 1923 addressing crop and livestock diversification to help farmer’s avoid the cycle of overproduction, price decline and waste. It was also why Coolidge would support the Tincher bill in 1926 to supply $100 million in revolving loans to co-operatives. Connecting the producer with the consumer, supplying capital where it was most needed and efficiently used, did more to aid farmers than any government price-plan could yield.

Second, President Coolidge identified the important part co-operatives played in handling “accidental surpluses.” No real solution should be made into a crutch, to incentivize purposefully wasteful overproduction or subsidize reckless decision-making on the part of farmers. Only reducing production could solve excessive supplies of any given crop. No proposal could replace the initiative or judgment of the individual farmer. Co-operatives, handling roughly one-fifth of total agricultural produce annually, were there not to supplant the sense people were to exercise for themselves. The co-operative was there to help when weather bestowed higher yields than expected. The farmer was not to lean upon the co-operative as his permanent safety net, substituting its storage and resources for his own failure to sow, cultivate and reap wisely.

“To have agriculture worth anything, it must rest on an independent business basis. It can not at the same time be part private business and part Government business. I believe the Government ought to give it every assistance, but it ought to leave it as the support, the benefit, and the business of the people…Government ought not to undertake to control or direct, it should supplement and assist all efforts in this direction.” As Coolidge masterfully demonstrated throughout his Administration, the greatest help government can render starts by removing itself — the biggest obstruction to initiative and independence — from participation in the market. Coolidge was not the laissez-faire “purist” that New Deal revisionists later depicted him to be. He knew no market was absolutely free and that limited regulation was a Constitutional mechanism. But, he also understand that government power was wisely and very properly confined by the Founders so that problems found solutions from the people themselves, looking to one another, instead of Washington, for answers. Explaining the legislation he endorsed for agriculture, President Coolidge sided not with the “artificial support” of prices but with whatever rested firmly in “sound economic principles.” “The fundamental soundness” of the bill for co-operative marketing “rests on the principle that it is helping the farmer to help himself.”

Charles L. McNary, of Oregon, and Gilbert N. Haugen, of Iowa, both Republicans, co-authored the bills bearing their names which advocated government controls on agriculture, mandating an “equalization fee,” and buying crops overproduced by American farmers to be resold at artificial prices on foreign markets.

Maintaining this conviction did not come from a lack of sympathy for the difficulties the farmer faced. The exact opposite was true, especially for Coolidge. The responsibilities of leadership demanded something more than simply indulging the short-sighted and mistaken wishes of the electorate, however politically powerful the “Farm Bloc” proved to be. It was not leadership to follow the misled and uninformed. Agriculture needed to “consider the encouraging features of their situation” not deny them, perpetuating a perception of crisis. “Human nature is on their side,” the President reminded them. “We are all consumers of food.” As Coolidge recapped the rise and fall of prices since 1820, historical perspective made clear that farming continued to advance, even the setback of 1921 was temporary. Agriculture was going to see a return. It was not, as George N. Peek opined, an “us versus them” mentality where industry was concerned, like when he asked “[S]hall agriculture exist merely to feed the mouth of industry?” President Coolidge could not disagree more. The growth of industry meant the progress of agriculture because we all have to eat.

George N. Peek, President of Moline Plow Company and tireless lobbyist on behalf of government joining with corporations to fix agricultural prices. After Coolidge thwarted his efforts to make McNary-Haugen the law, Peek became a Democrat and, eventually, a supporter of FDR’s Agricultural Adjustment Act.

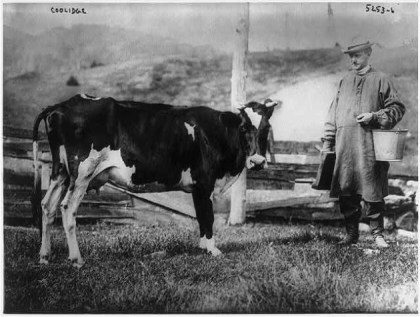

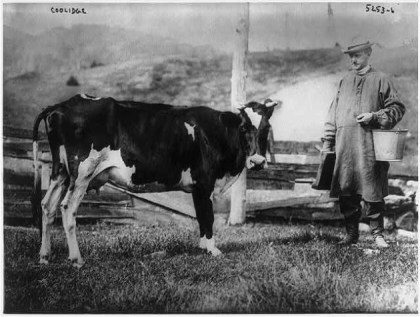

Our economy had not been built overnight. It was the result of incremental effort by every part of the Nation’s economy. As the other areas of economic endeavor prospered, what the farm produced would only increase exponentially to meet demand. At the head of it all would be the farms and ranches across America who would lead because everyone requires what they produce. After all, as the President reiterated, the farm is not only the source of food nor is it merely in the pursuit of material aims. “The ultimate result is…the making of people. Industry, thrift, and self-control are not sought because they create wealth, but because they create character. These are the prime product of the farm. We who have seen it, and lived it, we know.”

In that high and noble purpose, the farm reconnects and renews the Nation with both a “true relation to nature” and an individual’s importance to the Divine Plan at work in this world. The blessings afforded by the farm have included “the life of freedom and independence, of religious convictions and abiding character. In its past it has made and saved America and helped rescue the world.” With these astounding accomplishments, it was no exaggeration for Coolidge to see the time ahead for America as still brighter yet. In upholding these principles cultivated through life on the farm, the future “holds the supreme promise of human progress.”

As the President departed so hastily he forgot to grab his overcoat, the chilly reception to his principles would continue in a protracted battle long after he left the White House. Two days later, Southern delegates led by Alabama would unseat President Bradfute and elect Sam H. Thompson, an Illinois farmer who had taken part in much of the legislative fight to pass McNary-Haugen the previous year and wanted to expedite its passage into law now. Bradfute had upheld his promise to encourage co-operative marketing and resist government manipulation of prices, “equalization fees” and all the accessories for Federal control of agriculture. The President’s determined leadership, even when the pressure to surrender to the McNary-Haugen bill rose to deafening levels, Coolidge remained on course because he knew he was right and that the people would come to understand that. His second veto would be the last word on the matter until Hoover conceded with the creation of the Farm Board, superficial price-boosting and a revived “equalization fee.”

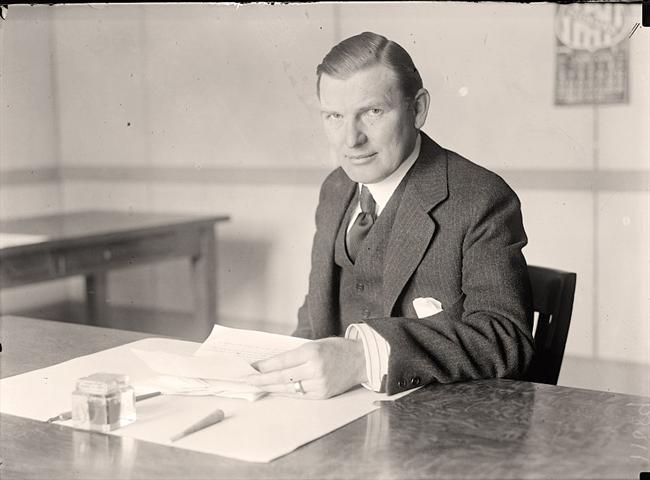

Newly elected President of the American Farm Bureau Federation, Sam H. Thompson, who would move to push McNary-Haugen all the way to President Coolidge’s desk in 1927.

For now, though, Coolidge fearlessly went into the arena, articulated the reasons why this popular trend toward government intervention in agriculture would fail, leaving the farmer worse under its provisions. Departing the room with his confident and unapologetic defense of rugged individualism and personal initiative still ringing in their ears, President Coolidge, a farmer, descended from a long line of farmers, walked from the Sherman Hotel a living confirmation that what he said was true: as long as agriculture maintains its independence from government’s attempts to “help.”

Coolidge, Calvin. “The Farmer and the Nation,” December 7, 1925, cited in Foundations of the Republic. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Fite, Gilbert C. George N. Peek and the Fight for Farm Parity: A vivid story of the farmers’ campaign for agricultural equality and of the man who led it. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1954.

Hansen, John Mark. Gaining Access: Congress and the Farm Lobby, 1919-1981. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1991.

Michigan Farm Bureau News, “Elect Sam Thompson President of American Farm Bureau,” http://archive.lib.msu.edu/DMC/MFN/1925/December%2018%201925.pdf.