“If some current statements are to be taken seriously we are expecting too much from free government…We demand entire freedom of action and then expect the government in some miraculous way to save us from the consequences of our own acts. We want the right to run our own business, fix our own wages and prices, and spend our own money, but if depression and unemployment result we look to government for a remedy.

“We insist on producing a farm surplus, but think the government should find a profitable market for it. We overindulge in speculation, but ask the government to prevent panics. Now the only way to hold the government entirely responsible for conditions is to give up our liberty for a dictatorship. If we continue the more reasonable practice of managing our own affairs we must bear the burdens of our own mistakes. A free people cannot shift their responsibility for them to the government. Self-government means self-reliance” — Calvin Coolidge, October 17, 1930

“When people are bewildered they tend to become credulous. We are always in danger of expecting too much of the government. When there is distress such expectations are enlarged…That is the danger now…A large expenditure of public money to stimulate trade is a temporary expedient which begs the question…Business does not need more burdens but less. The sound way to relieve distress is by direction action [by people themselves]…The people have more power than any government to restore their own prosperity” – November 28, 1930

“Some confusion appears to exist in the public mind as to the proper function of the national government in the relief of distress, whether caused by disaster or unemployment. Strictly construed, the national government has no such duties. It acts purely as a volunteer…In the case of unemployment, relief is entirely the province of the local government which has agencies and appropriations for that purpose…Every government should spend its own money. Otherwise the appropriating agency has no control over the disbursing agency and no check on extravagance” – December 5, 1930.

“…[I]nstead of letting the market take its own course there is always a great temptation to try some artificial remedy. Of late this has run to the device of having the public treasury assume in some way the burden of absorbing the losses of those who have suffered. It is the duty of the government to provide highways and waterways…But local government must relieve the needy. In the general field of business, whether of industry or agriculture, government interference in an attempt to maintain prices out of the treasury is almost certain to make matters worse instead of better. It disorganizes the whole economic fabric. It is a wrong method because it does not work. It is better for every one in the end to let those who have made losses bear them than to try to shift them on to some one else. If we could have the courage to adopt this principle our recovery would be expedited. Price fixing, subsidies and government support will only produce unhealthy business” — December 22, 1930.

“Another proposal to be made in the name of relieving unemployment will undoubtedly be an extension of government ownership…The government has never shown much aptitude for real business…The most free, progressive and satisfactory method ever devised for the equitable distribution of property is to permit the people to care for themselves by conducting their own business. They have more wisdom than any government” — January 5, 1931.

“Left alone without the paralyzing interposition of the government, the people have a better opportunity for progress, prosperity and happiness than can ever be secured from any official bureau” – March 27, 1931.

“With the convocation of representatives of various lines of industry have come proposals for controlling and standardizing business. Almost all these suggestions are for artificial rules of conduct to save a situation from the inevitable consequences of the force of natural laws. If business is to be controlled from the outside, the liberty of action and power of initiative will be greatly circumscribed. If standardization is adopted in its entirety, the result is rigid fossilization which prevents progress. Neither the state nor the Federal governments can supply the information and wisdom necessary to direct the business activity of the nation…The experience, skill and wisdom necessary to guide business cannot be elected or appointed. It has to grow up naturally from the people. The process is long and fraught with human sacrifice, but it is the only one that can work” — May 1, 1931.

“In the end the security of nations and men must be sought within themselves by observing the command to do justice, love mercy and walk humbly” — May 12, 1931.

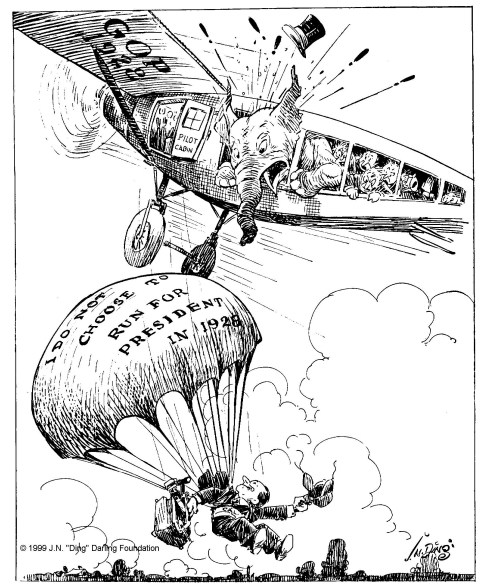

“The centralization of power in Washington, which nearly all members of Congress deplore in their speech and then support by their votes, steadily increases…The farmer who was the shining example of sturdy independence has intrusted the government with finding him a market. Now the wage earner is to look to the same source to find employment. Individual self-reliance is disappeared and local self-government is being undermined.

“A revolution is taking place which will leave the people dependent upon the government and place the government where it must decide questions that are far better left to the people to decide for themselves. Finding markets will develop into fixing prices, and finding employment will develop into fixing wages. The next step will be to furnish markets and employment, or in default pay a bounty and dole. Those who look with apprehension on these tendencies do not lack humanity, but are influenced by the belief that the result of such measures will be to deprive the people of character and liberty” – June 20, 1931.