Today marks two historic occasions. The second is better known and, while far more expansive a triumph than the first, it gives further validation to the first. That second occasion is, of course, the Allied Invasion of Normandy, 1944, establishing a beachhead from which to advance inland that led to the liberation of France, the defeat of the Nazi regime, and the rescue of Western Europe by the United States military and our allies across Europe, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Lesser known were the actions of the 332d Fighter Group, the Tuskegee Airmen, in the Mediterranean and northward, as they contributed significantly to the push inland to meet those heading south from Normandy. Still, lesser known are the actions of the 2d Cavalry Division, the 92d and 93d Infantry or the numerous armored and artillery units as well as the 51st and 52d Defense Battalions in the Marine Corps who served in every theater of the Second World War just as courageously as the countless other units of our military. The men who comprised those units, contrary to many who assume racism prevented such occurrences, were what we now dub, “African-Americans” or “minorities.” They would fight alongside the other units scrapping their way across Europe to get to Berlin and defeat the Third Reich. These brave men and women echoed the testament of real progress demonstrated in World War I by 350,000 volunteers in the armed forces, including the illustrious 369th Infantry.

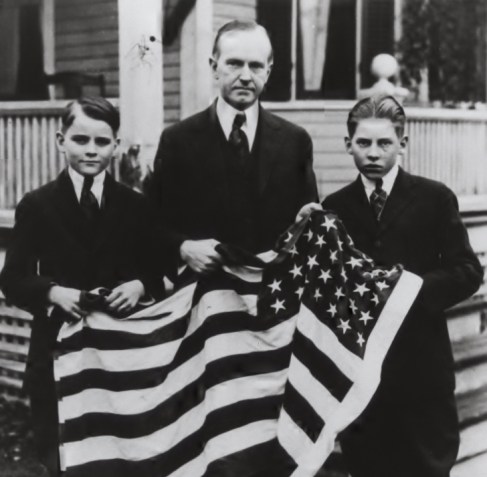

The first occasion was President Coolidge’s speak at Howard University on this day in 1924. On that day he would express his thoughts on the progress of “black Americans” since emancipation, sixty-one years before. Considering the entire span of human history, Coolidge lauded the tremendous advancements of so brave and worthy a people when it took hundreds of years for “white men” to grow from slavery to liberty. They had accomplished it in less than one hundred years. Where most saw poverty and permanent dependence for the “African-American,” Coolidge saw immense potential. In a very real way, he saw more promise in them than they now recognize in themselves. Where many still see unending racism and deprivation, Coolidge kindly points the way to greater progress and opportunity.

First. Coolidge would tabulate the genuine marks of economic growth that had come to these fellow citizens,

“Looking back only a few years, we appreciate how rapid has been the progress of the colored people on this continent. Emancipation brought them the opportunity of which they have availed themselves. It has been calculated that in the first year following acceptance of their status as a free people, there were approximately 4,000,000 members of the race in this country, and that among these only 12,000 were the owners of their homes; only 20,000 among them conducted their own farms, and the aggregate wealth of these 4,000,000 people hardly exceeded $20,000,000. In a little over half a century since, the number of business enterprises operated by colored people had grown to near 50,000, while the wealth of the Negro community has grown to more than $1,100,000,000. And these figures convey a most inadequate suggestion of the material progress. The 2,000 business enterprises which were in the hands of colored people immediately following emancipation were almost without exception small and rudimentary. Among the 50,000 business operations now in the hands of colored people may be found every type of present-day affairs. There are more than 70 banks conducted by thoroughly competent colored business men. More than 80 per cent of all American Negroes are now able to read and write. When they achieved their freedom not 10 per cent were literate. There are nearly 2,000,000 Negro pupils in the public schools; well-nigh 40,000 Negro teachers are listed, more than 3,000 following their profession in normal schools and colleges. The list of educational institutions devoting themselves to the race includes 50 colleges, 13 colleges for women, 26 theological schools, a standard school of law, and 2 high-grade institutions of medicine. Through the work of these institutions the Negro race is equipping men and women from its own ranks to provide its leadership in business, the professions, and all relations of life.”

Howard University was and remains a monumental contributor to that calling of advancement, starting with the mind and soul through education. Coolidge was not naive to the prospect of eradicating all future difficulties, for, he continued, “Racial hostility, ancient tradition, and social prejudice are not to be eliminated immediately or easily. But they will be lessened as the colored people by their own efforts and under their own leaders shall prove worthy of the fullest measure of opportunity.” Have today’s leaders fulfilled that high calling envisioned by Coolidge?

The President would drive the point home by recalling the countless sacrifices of life and security by over than 2,250,000 individuals who volunteered.for service in the First World War. The cause of liberty compelled them just as strongly as it did all those who willingly gave of themselves for the ideals of America. Coolidge knew they served and sacrificed for ideals, not just the reality of life at home, even with the gains of economic benefit he noted earlier. They were Americans all, possessing the full blessings and rights of citizenship. It is on this day, with the memory of so many who fought and gave their all, that Coolidge would reflect with pride and love for an America that made all this possible. So many suffer abuse and misuse around the world, denied the opportunity to experience their God-given potential. Coolidge reminds us to appreciate the doors opened for the first time in human history when America has given people, of all backgrounds, the opportunity to thrive and reap the rewards of their own efforts. Do we have the confidence and determination to realize the potential Coolidge saw possible for us?