A quality well-known to those who knew him was Mr. Coolidge’s humility. He knew, as he wrote to his father, being “the most powerful man in the world,” meant high responsibilities not lofty privileges. It was not an opportunity to “live large,” clothing himself in the trappings of his glory. During his lifetime, he had seen certain men become President only to equate the majesty of the Office with the excellence of the person. He knew the dangers of arrogance. He was never fooled to think that it was proper, even for a President, to govern by the force of his personality. He had seen President Wilson try and disastrously fail on that score. Mr. Coolidge raised the dignity of the office during his time, that is for sure, but he distinguished between the greatness of the Presidency from the absence of greatness in him. He was simply chosen from the sovereign people to serve for a short time and then “be one of them again.”

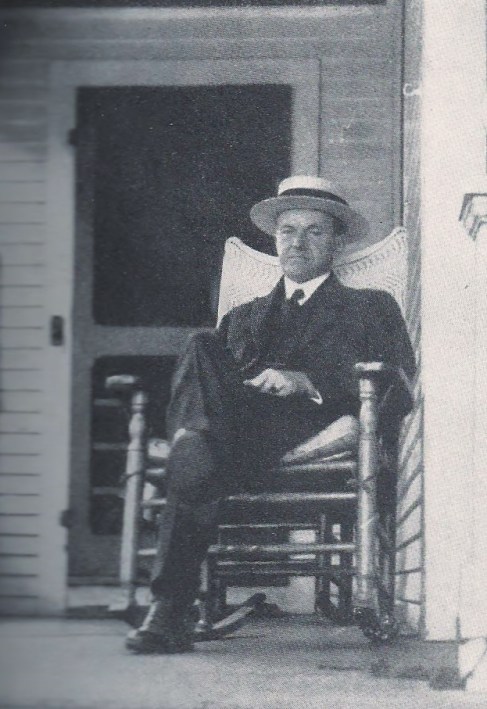

His desire to be a private citizen again was unfortunately never entirely restored. It cannot be easy to rediscover “normalcy” for anyone who has once been a President. But he earnestly tried. Prompted to speak in retirement, he accepted only under the most compelling pressure because he refused to accept it was his place to assume the mantle again as a kind of unofficial public authority or “Deputy President.” His humility was such that he could no longer do many of the things he loved to do, such as sit on his front porch. He disdained the ostentatious displays of attention showered on him because of the Presidency. He would tolerate it for the sake of the Office while he held it, but he refused to suffer it after the White House.

He disapproved of Presidential pensions and would not take a cent of public support. He would work for himself. It was writing that primarily occupied his time and even that weighed on his mind with the obligations of producing a product worth publishing, meeting deadlines, and not taking advantage of the credentials he could have claimed to accept more than a piece was worth.

His long-time law partner, Mr. Hemenway, recalled three occasions of Mr. Coolidge’s many expressions of simple unaffectedness, the first one in the midst of being President, that underscored his persistent humility. Mr. Hemenway, writing for Good Housekeeping in April 1935, recounts:

“While he was President, I had a note in longhand from him one day, as follows:

Sept. 13, 1928

‘My Dear Mr. Hemenway:–

‘You have at Hampton safety deposit 2 Lib Bonds $50 each. See if any are due Sept 15

current and if so have Tr. Co. collect them and credit my acct.

‘Yours

‘Calvin Coolidge’

“That note shows his far-reaching recollection of detail. Here you witness the President of the United States, the problems of a nation on his desk, with an income of $75,000 a year and $25,000 more for traveling expenses and entertainment, plucking out of his innumerable mental pigeonholes the relatively insignificant matter of two $50 Liberty bonds on which the interest of $2.12 was due!

“To show his kind-heartedness and his liberality I recall one occasion when I was in need of funds owing to the closing of a local bank. I was seated at my desk deeply buried in thoughts that were not particularly cheerful when he came through the connecting doorway from his office, walked over to me, and placed a slip of paper on my blotter. As he turned away and went back to his room, he said quietly,

‘And as much more as you want.’

“It was a check for $5,000.”

The final memory shared by Mr. Hemenway humorously highlights the former President’s unchanged outlook after life in the White House.

“The splendor and pomp of Washington and the Presidency never changed his early valuations of life. He was simple and unaffected to the last degree. He liked foot comfort. In the old days he would slip off his shoes and put both stockinged feet in his wastebasket where they wouldn’t be seen. Once, however, he was taken off his guard. A woman client came into his office while he feet were planted in the wastebasket. He got a good laugh out of it afterward–although he certainly did not enjoy the surprise at the moment.”

“We draw our Presidents from the people. It is a wholesome thing for them to return to the people. I came from them. I wish to be one of them again…They have only the same title to nobility that belongs to all our citizens, which is the one based on achievement and character, so they need not assume superiority. It is becoming for them to engage in some dignified employment where they can be of service as others are” — Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography, 1929, pp.242-3.