Though Calvin Coolidge preceded most of the “culture war” in which we are now surrounded, the roots of its existence were on the move in subtle ways in his time, particularly in higher education. The instigators of political correctness, always an intolerant and discontented minority, have rewritten much of our history, overturned the true meaning of our institutions and traditions and are well underway toward stripping the remaining vestiges of basic moral standards, and thus the political and economic liberties, from anything approaching an outward manifestation. The sanctity of religious freedom, the rights of individual conscience, upon which this New World was established finds itself under assault in ways never before known in America.

Though Calvin Coolidge preceded most of the “culture war” in which we are now surrounded, the roots of its existence were on the move in subtle ways in his time, particularly in higher education. The instigators of political correctness, always an intolerant and discontented minority, have rewritten much of our history, overturned the true meaning of our institutions and traditions and are well underway toward stripping the remaining vestiges of basic moral standards, and thus the political and economic liberties, from anything approaching an outward manifestation. The sanctity of religious freedom, the rights of individual conscience, upon which this New World was established finds itself under assault in ways never before known in America.

The trail of tyrannical violence by government suppression and mandated conformity in the Old World is well-worn and readily witnesses to how unjust and evil a series of crimes it perpetrates, regardless of who holds the reigns of power, against every individual to come under its wrenching grasp. America was the exception to this rule. Learning from history’s wealth of experience, our ancestors confirmed for any and all who would come after them the blessings of self-government, a framework of checks upon the power of government and protections upon the freedom of the individual, made possible by each person’s practice of virtue and informed citizenship. Being a full participant in the freedoms America has to offer requires first a sober acceptance of its obligations. It is not a tolerance of lawlessness or an undermining of the institutions that preserve responsible liberty. It means concrete standards of decency and morality must be met.

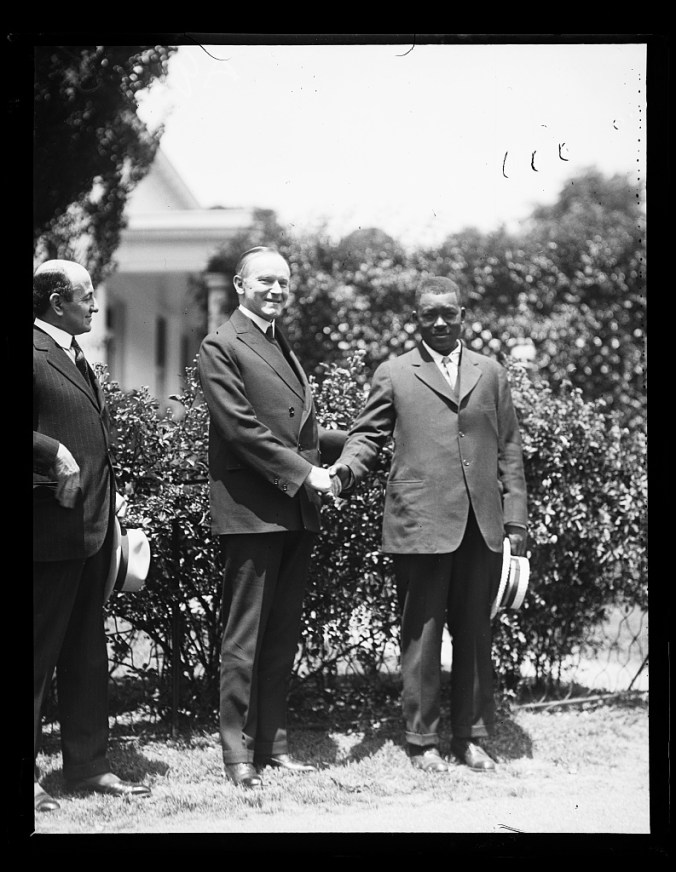

Mississippi River hero Thomas Lee, in saving the lives of those caught under the capsized steamboat M. E. Norman was honored by President Coolidge, May 28, 1925

The power accorded political correctness has taken on an authority even more potent and intrusive than many of our statutes, codes, customs and charters. This is a perversion of America’s extraordinary foundations and, ultimately, a repudiation of lawful and orderly self-government for the absolute control by a few self-appointed guardians. These gatekeepers are not content to simply agree to disagree but deploy the full powers of every branch of government to eliminate any action, any behavior and, as we now see, any word or even thought which fails to accord with their imaginary view of the world. It is a control so expansive in scope and so insidious in aim that despots from the “Reign of Terror” under Robespierre to the “sterilizations” under Soviet direction could not have better prepared the ground for absolute tyranny as well as the members of the American Left have in education, politics, journalism and popular culture over the past eighty years.

It was nowhere near the full-blown warfare against a free conscience and Christian morality that it is now, but Coolidge’s words on October 6, 1925, could be speaking to the current intolerance of political correctness that presides over every corner of Americans’ lives. As with any mere opinion, political correctness possesses the power we give to it. Though long ago, Coolidge still speaks because the nature of humanity has not progressed beyond itself. It is still struggling with the same fundamental problems of relating to others with which we may disagree. The problem is hardly a new one. Everyone has always had differing opinions, divergent convictions. What is relatively new is that some opinions are less worthy than others to even deserve utterance for nothing more than the superficial basis of skin color, political affiliation and religious belief. Merely the chance that someone somewhere is offended silences any further comment. It is now granted to a select few, living to be offended, to suppress and destroy dissent however benign or logical it is.

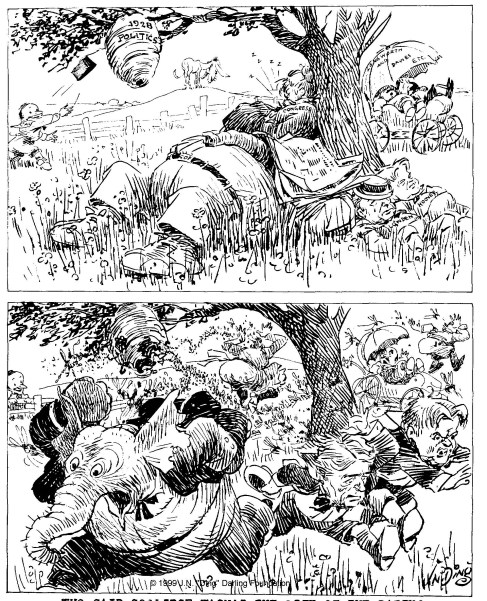

The Coolidges meet Progressives Mother Jones and Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., at the White House in 1924.

It was no less the man who has come to be called “Silenced Cal” because of the decades-old attacks to his credibility, accomplishments and character, who declared,

“Progress depends very largely on the encouragement of variety. Whatever tends to standardize the community, to establish fixed and rigid modes of thought, tends to fossilize society. If we all believed the same thing and thought the same thoughts and applied the same valuations to all the occurrences about us, we should reach a state of equilibrium closely akin to an intellectual and spiritual paralysis. It is the ferment of ideas, the clash of disagreeing judgments, the privilege of the individual to develop his own thoughts and shape his own character, that makes progress possible. It is not possible to learn much from those who uniformly agree with us. But many useful things are learned from those who disagree with us; and even when we can gain nothing our differences are likely to do us no harm.

“…It is not easy to conceive of anything that would be more unfortunate in a community based upon the ideals of which Americans boast than any considerable development of intolerance as regards religion. To a great extent this country owes its beginnings to the determination of our hardy ancestors to maintain complete freedom in religion. Instead of a state church we have decreed that every citizen shall be free to follow the dictates of his own conscience as to his religious beliefs and affiliations. Under that guaranty we have erected a system which certainly is justified by its fruits. Under no other could we have dared to invite the peoples of all countries and creeds to come here and unite with us in creating the State of which we are citizens” (emphasis added).

Marked for newspaper formatting, this photograph was taken upon President Coolidge’s honorary induction into the Sioux, 1927. Dubbed Wamble-To-Ka-Ha (Chief “Leading Eagle”), Coolidge was gifted the ceremonial headdress he is wearing. One of the Sioux chiefs said to Coolidge, “They tell us you are the thirtieth President of this great country, but to us you are our first President.”

Calvin Coolidge understood that the greatest threat to our system of freedom came not through foreign invasion or even a direct political coup, it came in the attack on the conscience and religious belief. Perhaps that is why the current minority engaging in orchestrated intolerance of Phil Robertson’s reasonably held convictions is so harmful to the peace and strength of America’s life. Threatened by a lone man’s views, they would muzzle and ostracize the person rather than meet him or her in the arena of ideas. Tolerant only of perfect conformity to their views, no one dares be so bold as to whisper a contrary notion. Unable to cope with ideas with which they do not agree, the solution is to turn loose the politically correct attack machine to so defame the latest dissenter that any future departures from the modern Left’s plantation of thought conformity are humiliated to silence.

The Founders in Federalist Numbers 48, 51 and 54, addressing the problem of majority versus minority rights strike upon the dangers that occur when a numerical minority obtains enough political power to dominate the numerical majority. This “elective despotism…was not the government we fought for,” Madison would assert in Federalist No. 48. Echoing the Federalist, Calvin Coolidge would warn of this very development in his time. We are now living that threat under Government by a few, maintained through the political correctness that subordinates and removes all competing ideas, not through reasoned exchange but through the very force of government imposed on the individual’s body, mind and soul.

Paramhansa Yogananda just after visiting with President Coolidge, January 24, 1927, during his visit to America. If you look closely over the Yogi’s right side, the President is taking one last look at his visitor through the window.

Coolidge said, “No minority is good enough to be trusted with the government of a majority.” It was why, as the authors of the Federalist explain, the broad differences of America’s people were to be encouraged and fostered, not stifled and denied. It would be a deadly thing when any minority assumed enough of the powers of government in a few hands to become a political majority, unrestrained in the arbitrary will of pure democracy that had destroyed the greatest civilizations in history. As constituted, our system of government allowed neither the minority nor the majority to assume control of the other, thereby denying rights not in the interest of whoever held control. In this way, power was to remain checked and liberty preserved. To give the balance to one over the other would end in despotism and, ultimately, an absence of any law or order at all.

President Coolidge dedicating the cornerstone of the Jewish Community Center, Washington, D.C., May 3, 1925.

Coolidge continued, “We have never seen, and it is unlikely that we ever shall see, the time when we can safely relax our vigilance and risk our institutions to run themselves under the hand of an active, even though well-intentioned, minority.” Coolidge was simply saying what the Founders understood from all of human history.

It was a truth, as Christian philosopher C. S. Lewis once observed, easily cloaked in the form of good intentions, when he said, “Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive.” For this reason, Patrick Henry would aver, “Guard with jealous attention the public liberty. Suspect everyone who approaches that jewel. Unfortunately, nothing will preserve it but downright force. Whenever you give up that force, you are inevitably ruined.” That force finds expression every time we stop empowering the politically correct few with the authority and legitimacy to dictate social, cultural and political rules for the rest of us outside our traditional and constitutional processes.

President Coolidge meeting Socialist Party activist Helen Keller, at the White House, January 11, 1926.

The Federal Government has already passed enough laws shackling people to a double standard, we have no moral imperative binding us to a systematic surrender of liberty before an amorphous and extra-legal “court” of political correctness. We can simply refuse to participate in the “game” of what others consider socially permissible at the current moment. The force to counter it, Coolidge would reiterate, is found in the individual, exemplifying the light of informed conscience, before the hostilities of an ignorant and hate-filled world. “In the end,” Coolidge, citing Scripture in his daily column on May 12, 1931, reaffirmed what both nations and individuals require: “to do justice, love mercy and walk humbly” (Micah 6:8). It means living the love of Christ, no less when it is met with prejudice and enmity. It means having the courage to restore moral standards to public life, “putting good government” back into the ballot box and exercising the duties, not merely the privileges, of self-governing citizenship.

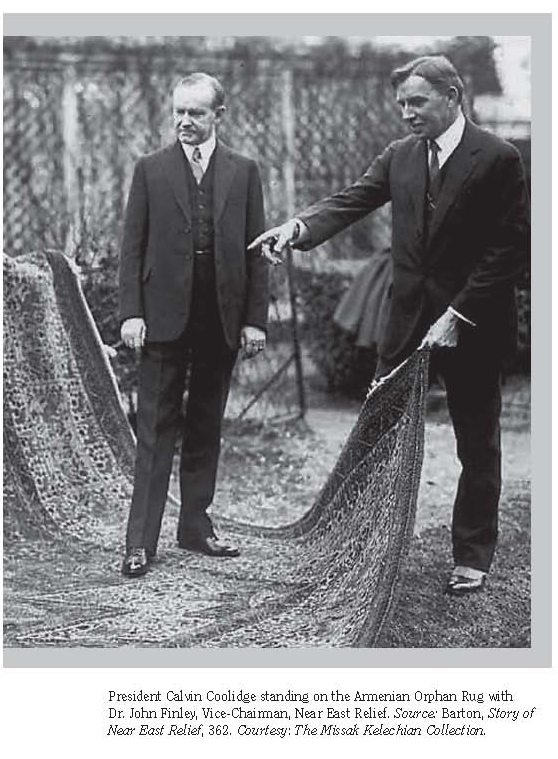

It was President Coolidge who graciously accepted the gift of this rug made by the Armenian orphans rescued by Americans from genocide under the Turks.

As Coolidge said in 1926, the Founders’ “intellectual life centered around the meeting-house. They were intent upon religious worship. While there were always among them men of deep learning, and later those who had comparatively large possessions, the mind of the people was not so much engrossed in how much they knew, or how much they had, as in how they were going to live. While scantily provided with other literature, there was a wide acquaintance with the Scriptures. Over a period as great as that which measures the existence of our independence they were subject to this discipline not only in their religious life and educational training, but also in their political thought. They were a people who came under the influence of a great spiritual development and acquired a great moral power.

“No other theory is adequate to explain or comprehend the Declaration of Independence. It is the product of the spiritual insight of the people. We live in an age of science and of abounding accumulation of material things. These did not create our Declaration. Our Declaration created them. The things of the spirit come first. Unless we cling to that, all our material prosperity, overwhelming though it may appear, will turn to a barren sceptre in our grasp. If we are to maintain the great heritage which has been bequeathed to us, we must be like-minded as the fathers who created it. We must not sink into a pagan materialism. We must cultivate the reverence which they had for the things that are holy. We must follow the spiritual and moral leadership which they showed. We must keep replenished, that they may glow with a more compelling flame, the altar fires before which they worshiped.”

Vice President Coolidge, just after taking the oath of office, is snapped next to Rebecca Felton, the overtly prejudiced Democrat Senator from Georgia, November 21, 1922.

A refusal to submit to the unlawful exercise of power is precisely what prompted the Founders to act and commended those actions to men like Coolidge, who understood what motivated them was not hatred, bigotry or selfishness. What compelled the Founders was the bulwark of religious freedom, the rights God gave the conscience of the individual, inspiring the men and women of that time to resist tyrants when they appeared. That same principle, in our hearts and minds now, has but to be exercised if genuine and constructive political corrections are to take place.