A Happy Columbus Day this 2025, as all (not merely selective parts) of history are reflected upon this weekend!

A Happy Columbus Day this 2025, as all (not merely selective parts) of history are reflected upon this weekend!

The shocking assassination of Charlie Kirk on September 10th marks a loss of something far more fundamental than a martyr for America’s heart and soul, beleaguered as it is in the latest phases of the culture wars. Far more elemental than hateful actions rendered proportionately in return for hateful speech, the murder of Kirk reveals a stark collision between despair and hope, the outright repudiation of classically liberal ideals, ones that have inspired acts of heroism and sacrifice from John Quincy Adams’ work on the Amistad case to Frederick Douglass’ efforts to break racial stratification before, during, and after 1865, which have been followed by principled actions of bold, patriotic Americans in countless situations since. The same spirit animated Martin Luther King to envision a world where the content of one’s character triumphed above a regime maintained by violent suppression.

The most radical reformers across every era of the American experiment, from Garrison to Bryan, or Debs to Malcolm X, have presupposed that rational persuasion remained the single most powerful means of changing outcomes as a result of changing minds. An order where killing becomes the sanctioned norm, a culture that remedies electoral losses with blood, silences dissent through terror rather than reason, and solves problems by replacing open debate with dehumanized slaughter of those with whom one differs was the antithesis of the optimism inherent in political activism. Abandoning the freedom to speak, shirking the call to reasonably discuss, respectfully differ, and artfully refute for the license to suppress and silence is a fundamental departure from America’s citizenship.

The ‘final solution’ of literally assassinating influential adversaries plunges America into the service of animalistic impulses while goosestepping away from every vestige of what it means to be human, living life for the betterment of humanity. It discards every shred of the liberating hope and once prevailing faith Americans of every background, creed, and color have possessed for more than three centuries. This is not merely a killing of an individual, it is the death of confidence in anyone or anything still remaining in America to change for the better. It is ultimately a barbaric breach of faith with the historic ability Americans have shown from the beginning to improve themselves, return to ideals, and meet problems squarely and courageously when presented with good reasons for doing so. The force of persuasion connected to shared essentials has always compelled Americans far more effectively than lawless coercion.

This is what made Kirk so impactful a rhetorician whose exercise to the fullest extent of the obligations of his citizenship will continue to shape the future. When he could have shirked the duty and avoided the risk, he entered the arena, gaining support not from the exercise of speech for hateful, selfish ends but for liberating and humanizing ones, appealing to those most ensnared in the intellectual, political, and cultural mires of his generation. That he proved more effective than his opposition in debate vindicated the potency citizenship contains when put to full use, an obligation cowardly skeptics and timid critics fail to realize in themselves or to recognize in others.

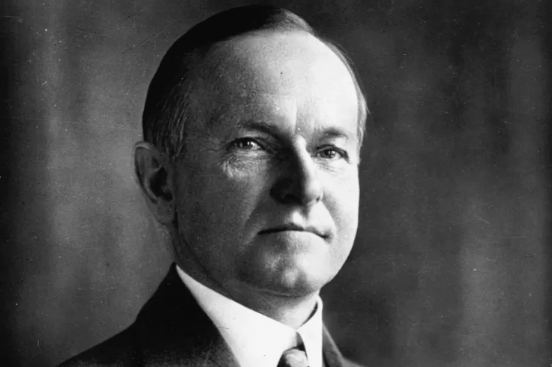

As a President Kirk himself greatly admired, Calvin Coolidge had much to say about employing those obligations of American citizenship to their utmost capacity. The failure to do so, whatever one’s political persuasion, was dereliction and betrayal of the trust it still is to be a citizen of the United States. As these excerpts from an address on April 14, 1924 attest, Coolidge delivers what many considered one of the greatest speeches of his career. Whatever one thinks of the late Charlie Kirk, he is certainly not to be found deficient in the full engagement citizenship demands of every American. His sense of decency, even in the midst of fierce debate, and courage in marshaling every resource to win the mind to rational discourse and the will to civic participation will renew the faith and hope that America, by definition, is.

“Institutions, whether adopted long ago or of more recent origin, are of themselves entirely insufficient. All of these are of no avail without the constant support of an enlightened public conscience. But still more is needed. Our only salvation lies also in the ever-present vigilant and determined action of the people themselves. The heroic thought and action of the Revolution must forever be supplemented by the heroic thought and action of to-day. Along with the great expansion of free institutions, which has carried them to all parts of the world in a startlingly brief historic period, there has gone a broadening of the principle of self-government. The ballot, in the earlier forms of democracy, was the privileged possession of a limited class. It was not looked upon as a right, but rather as the reward of some kind of high achievement, perhaps material, perhaps intellectual. But lately we have come upon times in which the vote is esteemed, not as a privilege or a special endowment bestowed only for cause shown, but more in the nature of an inherent right withheld only for cause shown. This new conception makes it no longer a privilege, no longer even a right which may be exercised or omitted as its possessor shall prefer. It becomes an obligation of citizenship, to be exercised with the highest measure of intelligence, thoughtfulness, and consideration for the public concern. The fundamental question of keeping America truly American is whether the obligation of citizenship is fully observed.

“Every voter ought not merely to vote, but to vote under the inspiration of a high purpose to serve the Nation. It has been calculated that in most elections only about half of those entitled to vote actually exercise their franchise. What is worse, a considerable part of those who neglect to vote do it because of a curious assumption of superiority to this elementary duty of the citizen. They presume to be rather too good, too exclusive, to soil their hands with the work of politics. Such an attitude cannot too vigorously be condemned. Popular government is facing one of the difficult phases of the perpetual trial to which it always has been and always will be subjected. It needs the support of every element of patriotism, intelligence, and capacity that can be summoned…

“[W]e have never seen, and it is unlikely that we ever shall see, the time when we can safely relax our vigilance and risk our institutions to run themselves under the hand of an active, even though well-intentioned, minority. Abraham Lincoln said that no man is good enough to govern any other man. To that we might add that no minority is good enough to be trusted with the government of a majority. And still further, we shall be wise if we maintain also that no majority can be trusted to be wise enough, and good enough, at all times, to exercise unlimited control over a minority. We need the restraints of a written constitution. To prevent the possibility of such things happening, we must require all citizens who are entitled to do so to take their full part in public affairs. We must be sure that they are educated, trained, and equipped to do their part well. We must not permit the mechanisms of government, the multiplicity of constitutional and statutory provisions to become so complex as to get beyond control by an aroused and informed electorate. We must provide ample facilities of education, and this will require constant expansion and liberalization. We must aim to impress upon each citizen the individual duty to be a sincere student of public problems, in order that they may rightly render the service which their citizenship exacts. But after all, good citizenship is neither intricate not involved. It is simple and direct. It is every-day common sense and justice.”