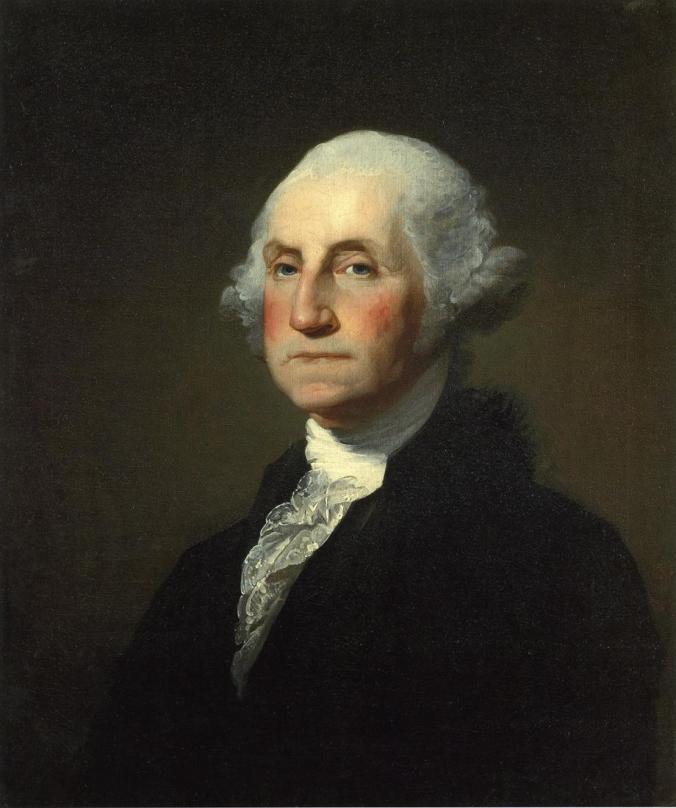

On August 20, we spoke of Calvin Coolidge’s thoughts on the limits of Presidential authority. It would be another twenty years before the passage of the Twenty-Second Amendment which codified President Washington’s self-imposed custom of serving only two terms. Attempted by a handful of previous Presidents, including the most recent third run of Theodore Roosevelt in 1912, it was actually shattered by Franklin Roosevelt in 1940, who would win a fourth term in 1944. After FDR’s death in 1945, Vice President Truman succeeded to the office as a majority of Americans had come to see the wisdom of Washington’s custom and move to protect it with Constitutional provision. Passing the Congress in March 1947, and securing final ratification by two-thirds (thirty-six) of the states on February 27, 1951, Section 1 of the Amendment made clear it would not apply to the current occupant, President Truman, declaring:

On August 20, we spoke of Calvin Coolidge’s thoughts on the limits of Presidential authority. It would be another twenty years before the passage of the Twenty-Second Amendment which codified President Washington’s self-imposed custom of serving only two terms. Attempted by a handful of previous Presidents, including the most recent third run of Theodore Roosevelt in 1912, it was actually shattered by Franklin Roosevelt in 1940, who would win a fourth term in 1944. After FDR’s death in 1945, Vice President Truman succeeded to the office as a majority of Americans had come to see the wisdom of Washington’s custom and move to protect it with Constitutional provision. Passing the Congress in March 1947, and securing final ratification by two-thirds (thirty-six) of the states on February 27, 1951, Section 1 of the Amendment made clear it would not apply to the current occupant, President Truman, declaring:

“No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice, and no person who has held the office of President, or acted as President, for more than two years of a term to which some other person was elected President shall be elected to the office of the President more than once. But this Article shall not apply to any person holding the office of President when this Article was proposed by the Congress, and shall not prevent any person who may be holding the office of President, or acting as President, during the term within which this Article becomes operative from holding the office of President or acting as President during the remainder of such term.”

Truman would be free to run again in 1952, but after losing the New Hampshire primary to Senator Kefauver, he reluctantly bowed out, announcing soon thereafter he would not be a candidate for another term. What one can do is not equivalent to what one should do.

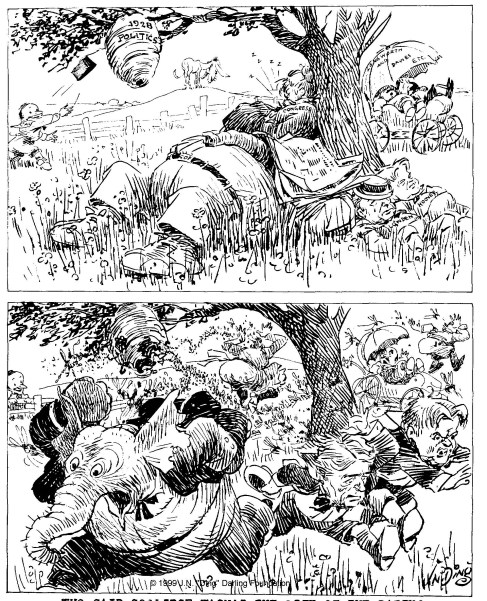

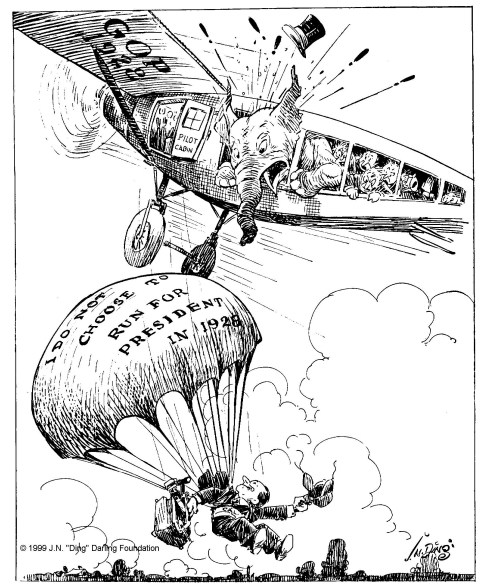

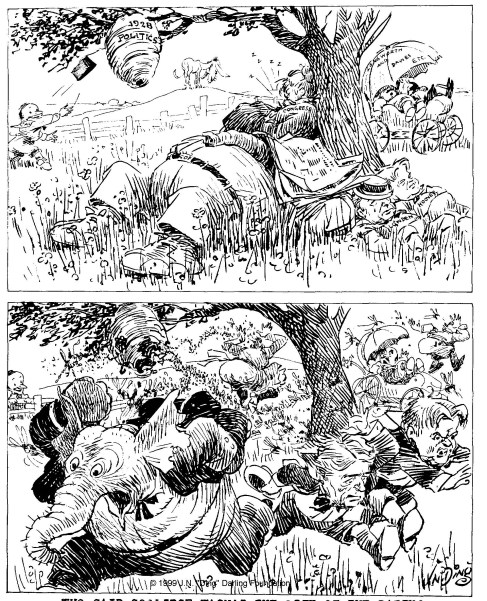

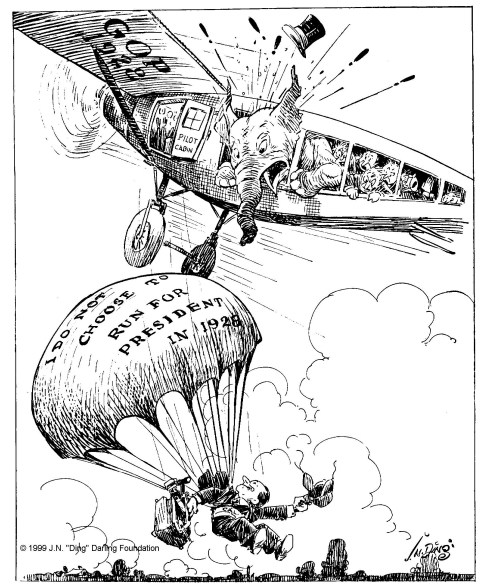

What did Coolidge have to say about the one hundred and thirty year example set by Washington? As already noted, it would be two decades before the passage of the Twenty-Second Amendment. However, it may come as a surprise to us now that talk of formal limits on a third term were gaining steam in the months leading up to Coolidge’s notorious press conference on August 2, 1927. Few Presidential statements caused as much uproar in those years as did his “I do not choose to run for President in nineteen twenty-eight.” Speculation was rampant as to what Coolidge actually meant and what he would do next. If he would not be the nominee, who would? Three interpretations quickly took shape, each explained by scholars Cyril Clemens and Athern Daggett in the June 1945 issue of The New England Quarterly. First, Coolidge neither wanted nor would accept renomination for the Presidency. Second, Coolidge, while not wanting the office, remained open to the prospect if the people renominated him. Third, Coolidge wanted to be President again but played politically coy to gain support.

Three interpretations quickly took shape, each explained by scholars Cyril Clemens and Athern Daggett in the June 1945 issue of The New England Quarterly. First, Coolidge neither wanted nor would accept renomination for the Presidency. Second, Coolidge, while not wanting the office, remained open to the prospect if the people renominated him. Third, Coolidge wanted to be President again but played politically coy to gain support.

The final interpretation, generally held by those who perceived him to be a conniving and selfish politician, like any other, attributes motives to the man that simply do not correspond to the facts. There was no question Coolidge would have had renomination unopposed in 1928. He had two, if not three, potential challengers heading into 1924, yet openly pursued the nomination at that time, even after tragically losing his youngest son and any pride he held for the “glory” of the Presidency. He had no reason to calculate for what was readily available to him four years later. But more to the point, his words and actions — in sum, his character — do not conform to this interpretation.

He meant what he said and his respect for the institutions and duties of the Office outweighed his own importance. He never saw himself as so great or indispensable that retaining power meant more to him than preserving the integrity of a very properly limited Presidential authority. He observed the virtue of self-control. It was through this self-imposed denial of executive power that the people were best served in their constitutional system. He had served his purpose, completing the work given for him to accomplish. The time had come for others to lead. It was indeed a wholesome thing to come back to the people from which he was drawn, serving as a private individual and nothing more. He knew that liberty is safeguarded when public servants know, and abide by, naturally imposed limits.

Some would mistakenly attribute a belief that serving four more years would constitute a violation of the “third-term policy” in Coolidge’s estimation. It did not. He had only served one full term and could legitimately stand for another. He made this plain in his Autobiography, “I do not think that the practice [no third term] applies to one who has succeeded to part of a term as Vice President.” If he had, Coolidge would have served ten years, longer than any other President up to that time. He would likely agree that Truman could have pursued a second term in 1952, while concurring that his choice to retire was the right one.

President Truman at the Jefferson-Jackson Dinner, March 29, 1952, at which he announced: “I shall not be a candidate for reelection. I have served my country long, and I think efficiently and honestly. I shall not accept a renomination. I do not feel that it is my duty to spend another 4 years in the White House.”

The strength of our Republic, Coolidge understood, never rested on the coercion of legislation. Not even a Constitutional Amendment could correct human nature, as was evident for all to see during the fourteen years of Prohibition enforcement. It relied on the surpassing might of moral rectitude and religious character in the heart of each individual. It was this which gave force to the legal and constitutional framework of our nation, not the other way around. Our system was a moral agreement. It would fail without virtue in the people and those it chooses to lead. Laws, like people, had natural limits. As Coolidge would say of the Eighteenth Amendment, “[A]ny law which inspires disrespect for the other laws — and good laws — is a bad law.” It would prove destructive if people ignored the wisdom of self-denial by empowering one man with authority for an unlimited time.

Writing as much for the future as for the present, former President Coolidge shared the same suspicions articulated by the Founders whenever people are entrusted with unconstrained power for indefinite periods of time. “A President should not only not be selfish, but he ought to avoid the appearance of selfishness. The people would not have confidence in a man that appeared to be grasping for office. It is difficult for men in high office to avoid the malady of self-delusion. They are always surrounded by worshipers. They are constantly, and for the most part sincerely, assured of their greatness. They live in an artificial atmosphere of adulation and exaltation which sooner or later impairs their judgment. They are in grave danger of becoming careless and arrogant. The chances of having a wise and faithful public service are increased by a change in the presidential office after a moderate length of time.”

As a Washington Post editorial is the latest in a line of calls to repeal the Twenty-Second Amendment, the argument is put forth that democratic choice has been somehow circumvented by term limits. Subjecting Presidents to third or fourth-term rejection by voters would rather supply a greater check upon their abuse of power than reinforcing Washington’s rationale, he asserts. After all the only reason for limits in the first place was political partisanship, the writer incorrectly assumes. We would ask whether this opinion writer at the Post would still maintain this argument if, as the original Amendment provided, it did not apply to the current occupant, who would still be bound to term limits? Party politics was not the reason self-applied term limitations were established over two centuries ago.

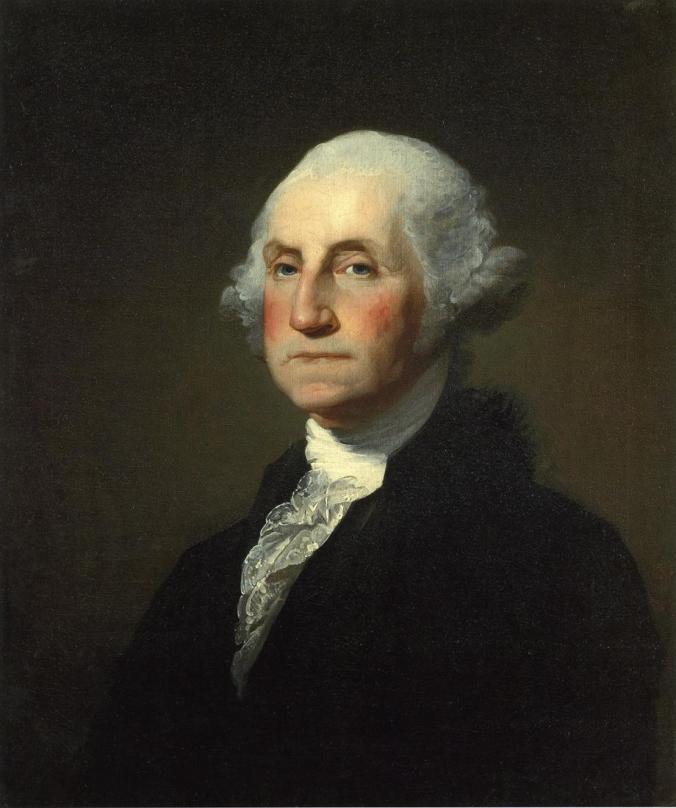

It is conveniently forgotten why Washington established this example, stating on that occasion,

“[I]t appears to me proper, especially as it may conduce to a more distinct expression of the public voice, that I should now apprise you of the resolution I have formed, to decline being considered among the number of those out of whom a choice is to be made…Satisfied that if any circumstances have given peculiar value to my services, they were temporary.”

For Washington, it was gratifying to him that “choice and prudence” invited him to lay down the Presidency. Though patriotic obligation did not forbid it, his wish to retire, wisdom and the people’s ability to choose did preclude it. These words, Coolidge later realized, were not unlike his own that August day in 1927. What one can do is not equivalent to what one should do. What is right for the country demands a subordination of self, these two men understood.

The power of the people to decide who leads is taken from them, whether a law exists or not, by the presumption that one man can be safely entrusted with additional power for an indeterminate time. “Emergencies” can be contrived and prolonged but experience confirms the soundness of Washington’s example. Even, as Coolidge pointed out, Presidential second terms have only served to confirm Washington’s sagacity. It is echoed in the self-denial of Coolidge, who surrendered the most powerful position in the world not because the law demanded it be done, though that would be reason enough for him. He surrendered its power because he approved of what Washington did, respected the credibility of the Office and subjected himself to the electoral judgment of the people. Free of a sitting President’s influence, however “in demand” he was, people could decide for themselves. They did so and vindicated the checks, even the “unwritten” ones, we impose on our leaders. He walked away gladly, relieved that America still regarded one of the most popular Presidents in history — himself — to be secondary to their commitment to limited government. As Clemens and Daggett ask, “Who can say that he did not choose wisely?”

The power of the people to decide who leads is taken from them, whether a law exists or not, by the presumption that one man can be safely entrusted with additional power for an indeterminate time. “Emergencies” can be contrived and prolonged but experience confirms the soundness of Washington’s example. Even, as Coolidge pointed out, Presidential second terms have only served to confirm Washington’s sagacity. It is echoed in the self-denial of Coolidge, who surrendered the most powerful position in the world not because the law demanded it be done, though that would be reason enough for him. He surrendered its power because he approved of what Washington did, respected the credibility of the Office and subjected himself to the electoral judgment of the people. Free of a sitting President’s influence, however “in demand” he was, people could decide for themselves. They did so and vindicated the checks, even the “unwritten” ones, we impose on our leaders. He walked away gladly, relieved that America still regarded one of the most popular Presidents in history — himself — to be secondary to their commitment to limited government. As Clemens and Daggett ask, “Who can say that he did not choose wisely?”

Outgoing President Coolidge, looking past the White House, to retirement, March 4, 1929