“We meet to dedicate a monument to the memory of the men of the First Division of the American Expeditionary Forces, who gave their lives in battle for their country. Their surviving comrades bestow this gift upon the Nation. It bears mute but enduring testimony of an affectionate regard for those who made the great sacrifice. This beautiful and stately shaft represents no spirit of self-glorification. It is a tribute of reverence and sorrow to nearly 5,000 of our immortal dead from those who knew and loved them. The figure of winged victory rises above the scrolls of imperishable bronze on which are inscribed alone the ennobled names of those who fell and through their deathless valor left us free. Other soldiers, generals and privates, officers and men, rank on rank, of illustrious fame are unrecorded here. They live. The dead reign here alone.

“This memorial stands as a testimony of how the members of the First Division looked upon the War. They did not regard it as a national or personal opportunity for gain or fame or glory, but as a call to sacrifice for the support of humane principles and spiritual ideals. This monument commemorates no man who won anything by the war. It ministers to no aspiration for place or power. But it challenges attention to the cost, suffering, and sacrifice that may be demanded of any generation, so long as nations permit a resort to war to settle their disputes. it is a symbol of awful tragedy. of unending sorrow, and of stern warning. Relieved of all attendant considerations, the final lesson which it imparts is the blessing of peace, the supreme blessing of peace with honor.

“The First Division has the notable record of being the first to enter France and the last to leave Germany. Hurriedly assembled, largely from Regular Army units, its first four regiments landed at Saint-Nazaire at the end of June, 1917, the advance guard which in a little more than a year was to be swelled to the incredible force of two millions. It had two battalions in the Grand Parade of July 4th in Paris, when tradition claims that a great American Commander laid our wreath at the tomb of the great Frenchman with the salutation which was short but all-embracing in its eloquence: ‘Lafayette, we are here.’ Other units, mostly from those who served in Mexico, made the Division so cosmopolitan that it represented every state and all the possessions of the Union. It was comprehensively and truly American.

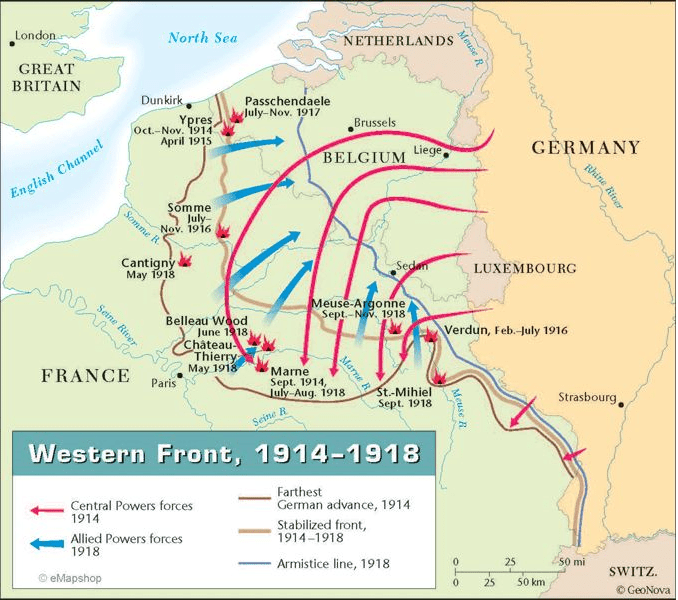

“After short and intensive preparation the Division was ordered from the Gondrecourt training area to the Sommerville sector, where on October 23rd the first American shot was fired. On October 25th the first American officer was wounded, and two days later the first prisoner was taken. On the night of November 2nd Corporal James B. Gresham and Privates Thomas F. Enright and Merle D. Hay, killed when their trenches were raided, were the first Americans lost in the war.

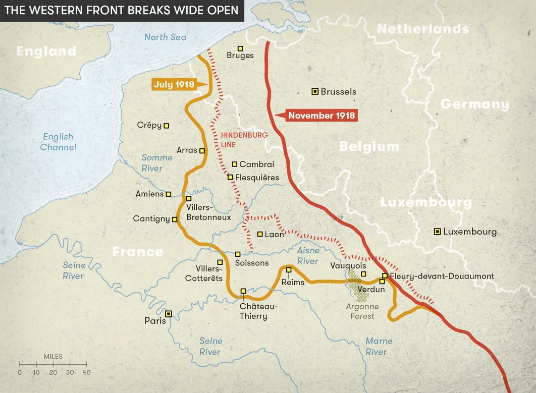

“In January, 1918, the Division was removed to the Toul sector, where for the first time Americans were given charge of a section of trenches. From here it was sent to Catigny sector to resist the March drive against Amiens. To this place General Pershing came on a personal visit, warning the officers of the desperate character of the fighting which was soon encountered. The trenches here were imperfect and the troops were constantly exposed to shellfire. The first offensive of an American unit was the attack on Catigny…In July the Division was placed in the Soisson sector to take part in the attack on the German salient. In five days of heavy fighting, it advanced 11 kilometers and captured 3,500 officers and men, with large quantities of materials. Its own losses were 78 officers and 1,458 men killed, 214 officers and 6,130 men wounded, 5 prisoners and 390 missing; a heavy price to pay, but the victory at Soisson has been called the turning point of the war.

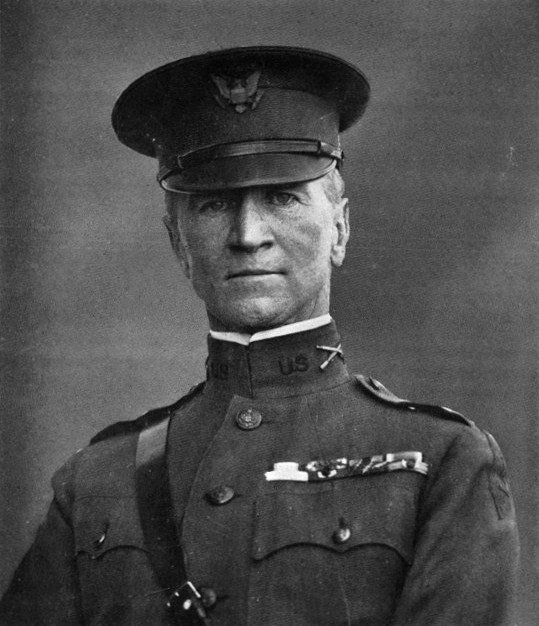

“Following a fortnight for rest and replacements a short service in the Vosges preceded the attack on St. Mihiel. The offensive against this position, which has been held for four years, was the first operation of an American army under an American commander. Under the direction of General Pershing nine American and some French divisions won complete victory, the Americans capturing 16,000 prisoners, 443 guns, and 240 miles of territory. The Division was then sent to the Meuse. In the great final offensive about a million American troops were engaged in the Argonne sector. After being held in reserve five days after operations opened, the First Division went into action October 4th to open the way on the east for a flank attack upon the forest. From then until the Armistice fighting and marching were continuous. The early successes of the American forces in the Argonne attack started a general German retirement about November 2nd. From then until Armistice Day the advance continued. On the night of November 5th, the First Division reached the Meuse. It was ordered to attack Sedan. Between 1630 in the afternoon of November 5th and midnight November 7th, the Division advanced and fought constantly. The 16th, 18th, and 28th Infantry Regiments covered 35 miles each, while the 26th Infantry, under the command of Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, traversed no less than 45 miles. Then came the Armistice. Immediately after the Division was ordered into Germany and stationed at the bridgeheads east of the line, from which it was withdrawn about a year later, the last units reaching New York on September 6, 1919.

“Such in barest outline is the war record of the First Division. In little more than a year it lost by death 5,516, of which 4,964 were killed in battle. Over 17,000 were wounded, 170 were reported missing, and 124 were taken prisoners. These numbers nearly equal the original strength of the Division. In General Order No. 201, of November 10, 1918, his only General Order issued referring exclusively to the work of a single Division, after describing your difficult accomplishments, General Pershing concluded thus: ‘The Commander-in-Chief has noted in this Division a special pride of service and a high state of morale, never broken by hardship or battle.’

“Five different Generals commanded the Division, all of whom won high distinction and commendation. They were William L. Sibert, Robert L. Bullard, Charles P. Summerall, Frank Parker, and Edward F. McGlachlin.

“The little that I can say in commendation of the service of your Division is but a slight suggestion of what is deserved. Every unit of the American Army, whether at home or abroad, richly merits its own full measure of recognition. They shrank from no toil, no danger, and no hardship, that the liberties of our country might adequately be defended and preserved.” — President Calvin Coolidge, dedication of the First Division Monument, American Expeditionary Force, President’s Park, Washington, October 4, 1924.

Happy Semiquincentennial to the United States Army!