Mr. Coolidge recognized the essence of good business was in strengthening ties of service and collaboration with others. He never saw the validity of an adversarial system, such as Bentham and the socialist economists espoused. Profit was important, of course, but not the supreme purpose of good business relations. He understood that business was about more than “crushing the competition.” It was about building bridges, not burning them. That is why he demanded a meeting with an apprehensive editor one afternoon. The editor had not published the entire number of articles agreed upon and written by the former President. Still, Mr. Coolidge had been paid for the entire set. The editor, bracing for confrontation, was shocked to find the former president wanted to meet in order to return the balance of the money due for the articles not published. To Coolidge, if they were not “good enough” to warrant publication, it would not be right to take money for them. In this way, good business is preserved.

The former President, writing another article on June 17, 1931, observed the necessity for “good business” to continue, especially as folks struggled to keep commerce going,

“It is a very sound business principle to let the other fellow make a profit. That was the essence of the slogan we heard a few years ago about passing prosperity around. The same thought is involved in paying good wages and fair prices. Cutting prices calls for cutting wages in the end.

“This is often the basis of the complaint against large concerns. When they control a large percentage of production they control the prices of the raw and unfinished materials used in that trade. They become almost the sole market for them. Under this condition there is a strong tendency in the name of efficiency and good management to squeeze out the small concerns furnishing these materials. But it is not usually good business.

“We are all so much a part of a common system of life that the business world is not healthy unless we all have a chance. A profit made by squeezing some one else out of a livelihood will almost surely turn up later as a loss. The great asset in trade is good will. The best producer of good will is the profit which others make” (emphasis added).

Month: April 2013

On Humility

A quality well-known to those who knew him was Mr. Coolidge’s humility. He knew, as he wrote to his father, being “the most powerful man in the world,” meant high responsibilities not lofty privileges. It was not an opportunity to “live large,” clothing himself in the trappings of his glory. During his lifetime, he had seen certain men become President only to equate the majesty of the Office with the excellence of the person. He knew the dangers of arrogance. He was never fooled to think that it was proper, even for a President, to govern by the force of his personality. He had seen President Wilson try and disastrously fail on that score. Mr. Coolidge raised the dignity of the office during his time, that is for sure, but he distinguished between the greatness of the Presidency from the absence of greatness in him. He was simply chosen from the sovereign people to serve for a short time and then “be one of them again.”

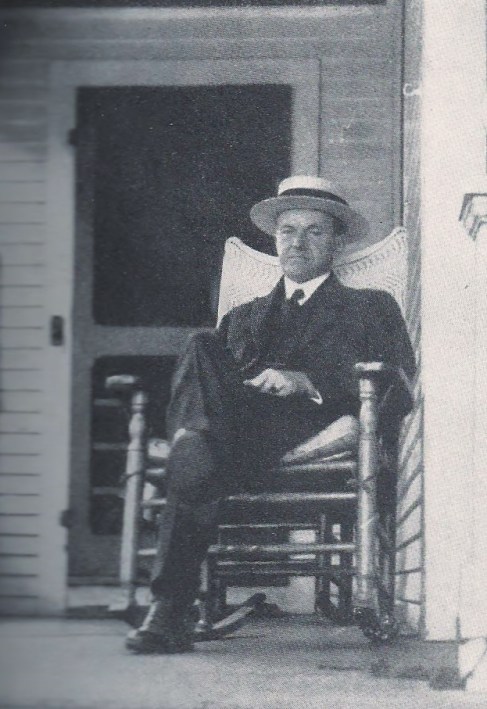

His desire to be a private citizen again was unfortunately never entirely restored. It cannot be easy to rediscover “normalcy” for anyone who has once been a President. But he earnestly tried. Prompted to speak in retirement, he accepted only under the most compelling pressure because he refused to accept it was his place to assume the mantle again as a kind of unofficial public authority or “Deputy President.” His humility was such that he could no longer do many of the things he loved to do, such as sit on his front porch. He disdained the ostentatious displays of attention showered on him because of the Presidency. He would tolerate it for the sake of the Office while he held it, but he refused to suffer it after the White House.

He disapproved of Presidential pensions and would not take a cent of public support. He would work for himself. It was writing that primarily occupied his time and even that weighed on his mind with the obligations of producing a product worth publishing, meeting deadlines, and not taking advantage of the credentials he could have claimed to accept more than a piece was worth.

His long-time law partner, Mr. Hemenway, recalled three occasions of Mr. Coolidge’s many expressions of simple unaffectedness, the first one in the midst of being President, that underscored his persistent humility. Mr. Hemenway, writing for Good Housekeeping in April 1935, recounts:

“While he was President, I had a note in longhand from him one day, as follows:

Sept. 13, 1928

‘My Dear Mr. Hemenway:–

‘You have at Hampton safety deposit 2 Lib Bonds $50 each. See if any are due Sept 15

current and if so have Tr. Co. collect them and credit my acct.

‘Yours

‘Calvin Coolidge’

“That note shows his far-reaching recollection of detail. Here you witness the President of the United States, the problems of a nation on his desk, with an income of $75,000 a year and $25,000 more for traveling expenses and entertainment, plucking out of his innumerable mental pigeonholes the relatively insignificant matter of two $50 Liberty bonds on which the interest of $2.12 was due!

“To show his kind-heartedness and his liberality I recall one occasion when I was in need of funds owing to the closing of a local bank. I was seated at my desk deeply buried in thoughts that were not particularly cheerful when he came through the connecting doorway from his office, walked over to me, and placed a slip of paper on my blotter. As he turned away and went back to his room, he said quietly,

‘And as much more as you want.’

“It was a check for $5,000.”

The final memory shared by Mr. Hemenway humorously highlights the former President’s unchanged outlook after life in the White House.

“The splendor and pomp of Washington and the Presidency never changed his early valuations of life. He was simple and unaffected to the last degree. He liked foot comfort. In the old days he would slip off his shoes and put both stockinged feet in his wastebasket where they wouldn’t be seen. Once, however, he was taken off his guard. A woman client came into his office while he feet were planted in the wastebasket. He got a good laugh out of it afterward–although he certainly did not enjoy the surprise at the moment.”

“We draw our Presidents from the people. It is a wholesome thing for them to return to the people. I came from them. I wish to be one of them again…They have only the same title to nobility that belongs to all our citizens, which is the one based on achievement and character, so they need not assume superiority. It is becoming for them to engage in some dignified employment where they can be of service as others are” — Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography, 1929, pp.242-3.

On Coolidge and the West

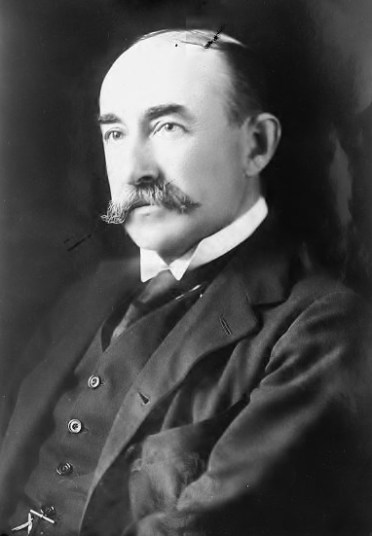

John Hays Hammond Sr. served as Chairman of the Coal Commission, as a coal strike threatened to be the first real domestic test of President Harding’s successor, Calvin Coolidge. Without coal, people were going to be hard-pressed to heat their homes and survive the cold winter. In what President Coolidge would call “our coup,” he collaborated with Commissioner Hammond to work out a way to resolve the conflict while shrewdly using the Governor of Pennsylvania, Gifford Pinchot (who was positioning himself as the heir of TR in order to take the GOP presidential nomination in the following year by championing his own progressive “handling” of the strike), as the implementer of their report. It worked only by removing imposed government solutions and turning to the folks directly concerned to make it succeed, all to the chagrin of Governor Pinchot.

Looking back on those days, Mr. Hammond offers this appraisal of President Coolidge and his impact on voters, especially those in the West. Most striking is that it runs contrary to the partisan and even vindictive appraisals of those who were denied special favor (like “Ike” Hoover, the usher) or had an agenda to implement (like “Art” Schlesinger). Hammond writes,

“It was most fortunate for the country that a man of Calvin Coolidge’s type succeeded to the presidency. He had an estimable record for probity and executive ability during both his Massachusetts governorship and the vice-presidency. Sitting in at Cabinet meetings during the Harding administration had given him special knowledge of national problems.

“His slightly rigid personality manifested caution and sanity. His eccentricities were safe ones. There was no derision in the anecdotes that were told of him, and the laughter of the people at hundreds of Coolidgisms only served to increase their belief in him as a wise and forceful leader. After the miasma of suspicion created by the scandals of the Harding administration, the country soon showed implicit confidence in Coolidge…”

Commissioner Hammond, a renowned mining engineer and native of California, assessed the affect of Coolidge on the West, “To me, as a Westerner who had grown to pride himself on his knowledge of the psychology of that part of the country, one of the most amazing things about Calvin Coolidge was that he came to supersede even Theodore Roosevelt in the popular affections of the West. Everything about Roosevelt had been the antithesis of Coolidge: his strenuous activities, his love of exciting adventures, his physical daring, his aggressiveness, and his ebullient manner. It has always seemed phenomenal to me that Coolidge, without any effort on his part, could have won the West. It may perhaps be explained by the fact that West admired Roosevelt as an individual and Coolidge as a president.”

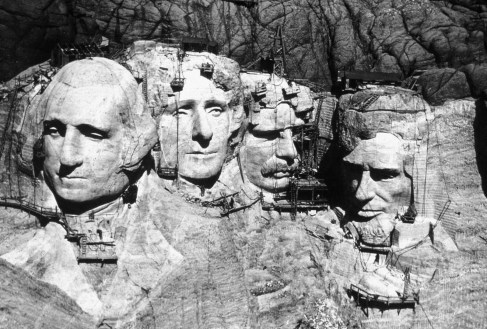

It is noteworthy that the only life-size statue of the thirtieth president stands in downtown Rapid City, South Dakota. It seems that Gutzon Borglum’s second mistake (after misusing President Coolidge’s written contributions to the Rushmore project) was in placing the wrong president to Lincoln’s right.